Closed reduction and casting techniques in fracture management

1 Closed reduction of fractures: Basic techniques (a): The direction and magnitude of the causal force (1) and the deformity (2) are related, and may be worked out from the history, the appearance of the limb and the radiographs. Any force required to correct the displacement of a fracture is applied in the opposite direction (3).

2 Basic techniques (b): The first step in most closed reductions is to apply traction – generally in the line of the limb (1). Traction will lead to the disimpaction of most fractures (2) and this may occur almost immediately in the relaxed patient under general anaesthesia. Traction will also lead to reduction of shortening (3), and in most cases to reduction of the deformity (4).

3 Basic techniques (c): Any residual angulation following the application of traction may be corrected by using the heel of the hand under the fracture (1) and applying pressure distally with the other (2).

4 Basic techniques (d): In some fractures there may be difficulty in reduction due to prominent bony spikes or soft tissue interposition. Reduction may sometimes be achieved by initially increasing the angulation prior to manipulation. This method of unlocking the fragments must be pursued with care to avoid damage to surrounding vessels and nerves.

5 Basic techniques (e): The effectiveness of reduction may be assessed by noting the appearance of the limb (1), by palpation, especially in long bone fractures (2), by absence of telescoping (i.e. axial compression along the line of the limb does not lead to further shortening) (3), and by check radiographs.

6. Basic techniques (f): After reduction of the fracture it must be prevented from redisplacing until it has united. The methods include the following:

7 Protection of the skin: Stockingette: A layer of stockingette is usually applied next to the skin (1). This has several functions: it helps prevent the limb hairs becoming caught in the plaster, it facilitates the conduction of perspiration from the limb, it removes any roughness caused by the ends of the plaster and it may aid in the subsequent removal of the plaster. After the plaster has been applied, the stockingette is turned back (2).

8 Stockingette ctd: After the stockingette has been reflected, excess is removed, leaving 3–4 cm only at each end (3). The loose edge of the stockingette is then secured with a turn or two of a plaster bandage (if a complete plaster is being applied) or with the encircling gauze bandage in the case of a slab.

9 Wool roll: A layer of wool should be used to protect bony prominences (e.g. the distal ulna). In complete plasters, where swelling is anticipated, several layers of wool may be applied over the length of the limb; the initial layer of stockingette may be omitted. A layer of wool may also be substituted for stockingette under a slab, and indeed many like to use a layer of wool under any type of cast. Wool roll is also advisable where an electric saw is used for plaster removal.

10 Felt: Where friction is likely to occur over bony prominences, protection may be given with felt strips or felt cut-outs, fashioned to isolate the area to be relieved (e.g. the vertebral and iliac spines, the pubis and manubrium in plaster jackets). Adhesive felt should not be applied directly to the skin if skin eruptions are to be avoided.

11 Plaster slabs (a): These consist of several layers of plaster bandage and may be used for the treatment of minor injuries or where potentially serious swelling may be anticipated in a fracture. In their application, slabs are cut to length (1), and trimmed as required (2) to fit the limb before being applied (3). Slabs may also be used as foundations or reinforcements of complete plasters.

12 Plaster slabs (b): If a slab dispenser is available, measure the length of slab required and cut to length. A single slab of six layers of bandage will usually suffice for a child. In a large adult, two slab thicknesses may be necessary. In a small adult, one slab thickness may be adequate with local reinforcement.

13 Plaster slabs (c): Alternatively, manufacture a slab by repeated folding of a plaster bandage, using say 8–10 thicknesses in an adult and six in a child as described (1). Turn in the end of the bandage (2) so that when the slab is dipped the upper layer does not fall out of alignment.

14 Plaster slabs (d): Ideally the slab should be trimmed with plaster scissors so that it will fit the limb without being folded over. For example, a slab for an undisplaced greenstick fracture of the distal radius should stretch from the metacarpal heads to the olecranon. It may be measured (1) and trimmed as shown, with a tongue (2) to lie between the thumb and index.

15 Plaster slabs (e): In a Colles fracture (see p. 196) where the hand should be placed in a position of ulnar deviation, the slab should be trimmed to accommodate this position, a stage that is often omitted in error. The preceding two plaster slabs are examples of dorsal slabs.

16 Plaster slabs (f): An anterior slab may be used as a foundation for a scaphoid plaster (see p. 209), or to treat an injury in which the wrist is held in dorsiflexion (measuring from a point just distal to the elbow crease with the elbow at 90°, to the proximal skin crease in the palm). The proximal end is rounded (1) while the distal lateral corner is trimmed for the thenar mass (2).

17 Plaster slabs (g): For the ankle (1) a plain untrimmed slab may be used, measuring from the metatarsal heads to the upper calf, 3–4 cm distal to a point behind the tibial tubercle. For the foot (2) where the toes require support, choose the tips of the toes as the distal point.

18 Plaster slabs (h): Owing to the abrupt change in direction of the slab at the ankle, the slab requires cutting on both sides so that it may be smoothed down with local overlapping. A back slab may be further strengthened by a long U-slab with its limbs lying medially and laterally.

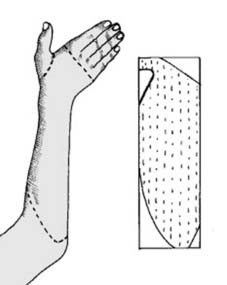

19 Plaster slabs (i): The same technique of side cutting is required for long arm plaster slabs (1). These are measured as indicated from the upper arm to the metacarpal heads, with a cut-out at the thumb as in a Colles plaster slab (2).

20 Plaster slabs (j): Wetting the slab: hold it carefully at both ends, immerse completely in tepid water, lift out and momentarily bunch up at an angle to expel excess water. Plaster-setting time is decreased by both hot and soft water.

21 Plaster slabs (k): Now consolidate the layers of the slab. If a plaster table is available, quickly place the slab on the surface and, with one movement with the heels of the hands, press the layers firmly together. (Retained air reduces the ultimate strength of the plaster and leads to cracking or separation of the layers.)

22 Plaster slabs (l): Alternatively, consolidate the layers by holding the plaster at one end and pulling between two adducted fingers (1). Repeat the procedure from the other edge (2).

23 Plaster slabs (m): Carefully position the slab on the limb and smooth out with the hands so that the slab fits closely to the contours of the limb without rucking or the formation of sore-making ridges on its inferior surface.

24 Plaster slabs (n): At this stage any weak spots should be reinforced. Where there is a right-angled bend in a plaster – for example at the elbow or the ankle – two small slabs made from 10 cm (4″) plaster bandages may be used as triangular reinforcements at either site. A similar small slab may be used to reinforce the back of the wrist.

25 Plaster slabs (o): In the case of a long-leg plaster slab, additional strengthening at the thigh and knee is always necessary, and this may be achieved by the use of two additional (15 cm) (6″) slabs.

26 Plaster slabs (p): Where even greater strength is required, the plaster may be girdered. For example, for the wrist, make a small slab of six thicknesses of 10 cm (4″) bandage and pinch up in the centre (1). Dip the reinforcement, apply, and smooth down to form a T-girder over the dorsum (2).

27 Plaster slabs (q): Girdering may also be achieved without a separate onlay. The basic plaster slab is pinched up locally after being applied to the limb. Care must be taken to avoid undue ridging of the interior surface.