Aftercare Complications The wrist and hand

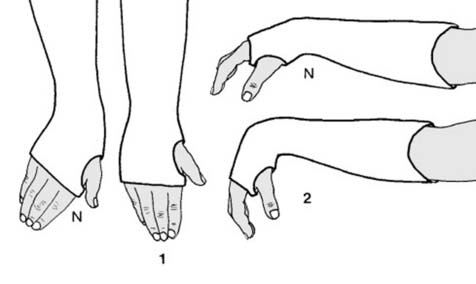

32 Aftercare (a): The patient is seen the next day and the fingers examined for adequacy of the circulation and the degree of swelling (1). The palm, fingers, thumb and elbow are checked for constriction caused by bandaging or elbow flexion, and any adjustments made (2). Thereafter the patient should be seen within the next 2-5 days with a view to completion of the plaster.

33 Aftercare (b): At the next review (usually a fracture clinic) finger swelling is checked: if slight, the plaster is completed (if marked, completion is delayed). Superficial layers of cotton bandage are removed, the slab retained, and encircling plaster bandages applied. The patient is instructed in elbow and shoulder exercises, and unless there is still a fair amount of swelling the sling may be discarded.

34 Aftercare (c): At 2 weeks the plaster is checked for marked slackening (replace), softening (reinforce) and technical faults (see next two frames). Movements in the fingers, elbow and shoulder are examined and appropriate advice given or physiotherapy started. In some centres radiographs are taken at this stage; slight slipping is inevitable, but marked slipping may be an indication for remanipulation (not usually a profitable procedure). At this stage too, if desired, the plaster may be replaced by a resin cast.

35 Aftercare (d): Positional errors: (1) The commonest fault is lack of ulnar deviation. This should be sadly accepted if discovered at 2 weeks (but replastered in the correct position if discovered earlier). Lack of ulnar deviation increases the risks of late problems arising from disruption of the inferior radio-ulnar joint; non-union of the ulnar styloid is common, with frequently some restriction of pronation and supination and local pain. (2) Excessive wrist flexion is liable to lead to difficulty in recovering dorsiflexion and a useful grip, and may be associated with compression of the median nerve. If present, the plaster should be re-applied with the wrist in a more extended position. (Full wrist flexion was once advocated in the treatment of Colles fracture – the Cotton-Loder position – but has been abandoned for the reasons given.)

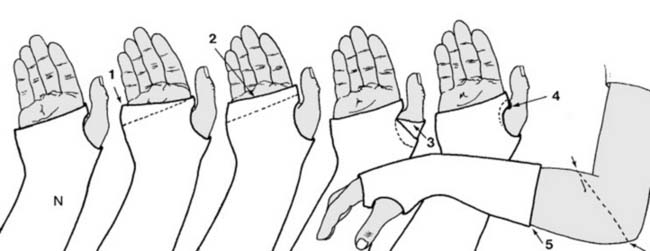

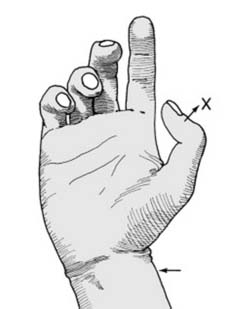

36 Aftercare (e): Plaster faults: Errors in plastering technique should not occur, but nevertheless are often discovered at this stage. The following faults are common: (1) The distal edge of the plaster does not follow the normal oblique line of the MP joints, and movements of the little and sometimes the ring finger are restricted. The plaster should be trimmed to the dotted line. (2) All the MP joints are restricted by the plaster which has been continued beyond the palmar crease. Trim to the dotted line. (3) The thumb is restricted by a few turns of plaster bandage. Again the plaster should be trimmed to permit free movement. (4) The plaster is digging into the skin of the first web and should be trimmed back to the dotted line. (5) The plaster is too short. Support of the fracture is greatly impaired; the plaster should be extended to the olecranon behind, and as far in front as will still permit elbow flexion.

37 Aftercare (f): The plaster should be removed at 5 weeks (or 6 weeks in badly displaced fractures in the elderly) and the fracture assessed for union. (Radiographs are of limited value.) If there is marked persisting tenderness, a fresh plaster should be applied and union re-assessed in a further 2 weeks.

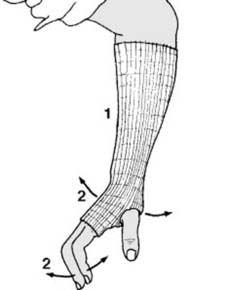

38 Aftercare (g): If tenderness is minimal or absent, (1) a circular woven support (e.g. Tubigrip™ or a crepe bandage) may be applied to limit oedema and to some extent increase the patient’s confidence. (2) The patient is instructed in wrist and finger exercises and encouraged to practise these frequently and with vigour. Arrangements are made to review the patient in a further 2 weeks.

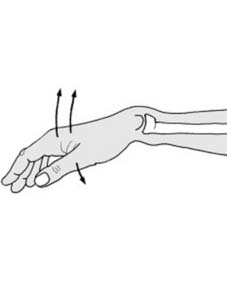

39 Need for rehabilitation (a): At about 7 weeks post injury, you must decide whether to discharge the patient or refer her for rehabilitation. Base your decision on: (i) finger movements, (ii) grip strength, (iii) wrist movements, (iv) the patient’s occupation. For example, 1. if finger ‘tuck-in’ (i.e. the last few degrees of flexion) cannot be carried out (loss Illus.) physiotherapy should be considered.

40 Need for rehabilitation (b): 2. Assess the patient’s grip strength by first asking her to squeeze two of your fingers as tightly as possible while you try to withdraw them. Compare one hand with the other. Repeat with a single finger. Marked weakness is an indication for physiotherapy.

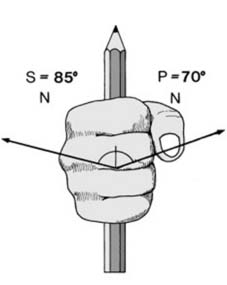

41 Need for rehabilitation (c): 3. Assess wrist movements. Initially, material restriction of palmar flexion is normal and by itself is of little importance. If, however, the total range of pronation and supination is less than half normal, physiotherapy is advisable. 4. Where there is only slight restriction of movements and power, rehabilitation may still be indicated through the special requirements of the patient’s work.

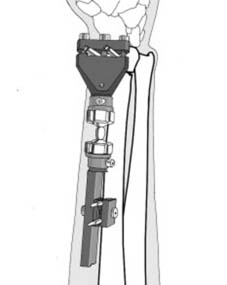

42 Alternative fixation methods (a): A Pennig Dynamic Wrist Fixator may be used where the fracture cannot be satisfactorily reduced or held by closed methods. Where the distal radial fragment is intact or occasionally with an undisplaced intra-articular fracture (AO = A2.2, A3.2, C1.2) pins are inserted in the distal fragment and the radial shaft. After assembly of the fixator, the fracture is reduced and the clamp screws locked. The wrist can be mobilised immediately.

43 Alternative fixation methods (b): Where there is severe comminution (Illus.), or splitting of the radial fragment into two or more displaced fragments an external fixator may also be used to bridge the fracture and the wrist joint. The distal pins are usually placed in the shaft of the second metacarpal. This allows control of length while avoiding the necessity of having to put the wrist up in marked flexion to maintain the reduction.

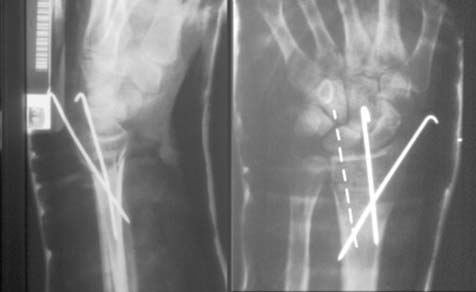

44 Alternative fixation methods (c): Where during a manipulative procedure instability is found to be marked, and it is considered that it will be very difficult to maintain any reduction with a cast alone, then the position may be stabilised with Kirschner wires. The most secure and reliable configuration1 is thought to be that of Kapandji (modified by Fritz et al) where a third K-wire is used. (Where this should be positioned is indicated by the dotted line on the radiograph above.) An additional plaster cast will be required until union of the fracture is well advanced. The wires may be removed after 3-4 weeks. In similar circumstances, plating of the fracture may also be considered. Anterior plates are most commonly used. A word of caution: the use of K-wires has been shown in the long term to offer no more than a marginal improvement on the radiographic appearances and overall function.2

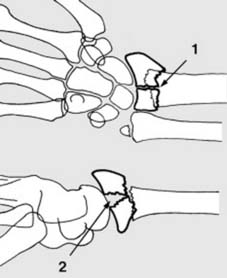

45 Splitting of the radial fragment (a): There may be a small vertical crack through the radial fragment, showing in the AP view (1). In others the fracture may run horizontally, and the scaphoid or lunate may separate the fragments (2). In the young adult, especially where the main fragments are separated and there is no gross fragmentation, internal fixation is indicated. (Barton’s fracture (see Frame 75) is similar, but with an intact posterior radial buttress.)

46 Splitting of the radial fragment (b): In a number of cases the fracture may be reduced under intensifier control (or under vision using an arthroscope). Kirschner wires may be used to lever the fragments into position prior to the insertion of the Kirschner fixation wires which are shown in this radiograph. Additional support with a cast will be needed. Some permanent joint stiffness is the rule after injuries of this pattern, and prolonged physiotherapy will usually be required.

47 Splitting of the radial fragment (c): Where comminution is not a problem, the distal fragments may be approximated with a cross screw (indicated by an arrow in the illustration). The distal radius may then be aligned with the shaft and held with a plate and screws. In this case a dorsal plate has been employed.

48 Splitting of the radial fragment (d): More commonly a pre-contoured volar plate may be used. This is first attached to the distal fragment with locking screws, resulting in the stem of the plate standing proud of the radial shaft. Levering it back into contact with the anterior surface of the radial shaft then leads to correction of the anterior angulation deformity. This technique may also be used with Colles pattern fractures uncomplicated by splitting of the distal fragment.

49 Splitting of the radial fragment (e): In some cases the degree of comminution or softness of the bone texture may render screw fixation in the distal fragments ineffective. In the case illustrated, although there are two reasonably substantial distal fragments, the horizontal line of the fracture is close to the joint leaving little bone for screw fixation. There is an additional vertical split in the radius.

50 Splitting of the radial fragment (f): In these circumstances the fracture was brought to length using a Pennig fixator, with pins in the radius and index metacarpal. The fragment which includes the styloid process was secured using two Kirschner wires, while the smaller medial fragment was held with an additional K-wire.

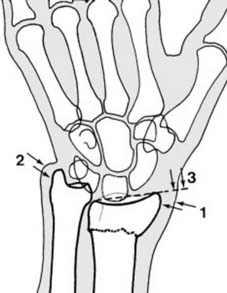

51 Complications (a): Persistent deformity or mal-union (i): Radial drift of the distal fragment results in prominence of the distal radius (1). Radial tilting and bony absorption at the fracture site lead to relative prominence of the distal ulna (2) and tilting of the plane of the wrist as seen in the AP radiographs (3). These deformities may be symptom free, and surgery on purely cosmetic grounds is seldom indicated.

52 Mal-union (ii): In some cases there is quite marked pain in the region of the distal radio-ulnar joint, owing to its severe disorganisation. There is generally quite marked local tenderness and supination in particular is reduced. Physiotherapy in the form of grip strengthening and pronation/supination exercises is indicated. If symptoms remain severe, excision of the distal end of the ulna may be considered.

53 Mal-union (iii): Uncomplicated persistence of dinner-fork deformity (i.e. persistent deformity in the lateral but not in the AP radiographs) is accompanied by some loss of palmar flexion, but significant functional disturbance is unusual. This type of residual deformity is generally accepted.

54 Complications (b):Delayed rupture of extensor pollicis longus may follow Colles fracture, and be due to attrition of the tendon by roughness at the fracture site, or by sloughing from interference with its blood supply. Disability is often slight, and spontaneous recovery may occur. There is no urgency regarding treatment, and in the elderly this complaint may be accepted or treated expectantly. In the young, an extensor indicis proprius tendon transfer is advocated.

55 Complications (c): Sudeck’s atrophy/complex regional pain syndrome: This is often detected about the time the patient comes out of plaster. The fingers are swollen and finger flexion is restricted. The hand and wrist are warm, tender and painful. Radiographs show diffuse osteoporosis (Illus.). Treatment. (1) The mainstay of treatment is intensive and prolonged physiotherapy and occupational therapy, but (2) if pain is very severe a further 2-3 weeks rest of the wrist in plaster may give sufficient relief to allow commencement of effective finger movements. (3) If the MP joints are stiff in extension and making no headway, manipulation under general anaesthesia followed by fixation in plaster (MP joints flexed, IP joints extended) for 3 weeks only may be effective in initiating recovery. (4) In severe cases, a sympathetic block may be attempted by infiltration of the stellate ganglion. (See Ch. 5 for a fuller discussion.)

56 Complications (d): Carpal tunnel (median nerve compression) syndrome: Paraesthesiae in the median distribution is the main presenting symptom, but look for sensory and motor involvement. If detected before reduction: (i) Complete lesion: reduce, plaster and re-assess. If no improvement, explore, and divide not only the roof of the carpal tunnel but the antebrachial fascia. (ii) Partial lesion: reduce and apply a cast; if motor symptoms remain, or if symptoms persist for a week, decompress.

57 Median nerve compression syndrome ctd: If detected after reduction: Release the splints, put the wrist in the neutral position, and use Kirschner wires or an external fixator to hold the reduction; if symptoms persist, explore. If detected after union: Exploration is generally advised, as symptoms otherwise tend to persist. Note that the diagnosis at the late stage may be suggested by the response to tapping over the nerve (Illus.), or by nerve stretching, tourniquet, or nerve conduction tests.