Pediatric Clavicle Fractures: Epidemiology, Anatomy, Clinical Evaluation, and Treatment

Learn about pediatric clavicle fractures, their epidemiology, anatomy, clinical evaluation, classification, treatment, and complications. Useful for healthcare professionals and parents alike.

Epidemiology

Most frequent long bone fracture in children (8% to 15% of all pediatric fractures).

These occur in 0.5% of normal deliveries and 1.6% of breech deliveries (they account for 90% of obstetric fractures). The incidence of birth fractures involving the clavicle ranges from 2.8 to 7.2 per 1,000 term deliveries, and clavicular fractures account for 84% to 92% of all obstetric fractures.

In macrosomic infants (>4,000 g), the incidence is 13%.

Eighty percent of clavicle fractures occur in the midshaft, most frequently just lateral to the insertion of the subclavius muscle, which protects the underlying neurovascular structures.

Ten percent to 15% of clavicle fractures involve the lateral aspect, with the remainder representing medial fractures (5%).

Anatomy

The clavicle is the first bone to ossify; this occurs by intramembranous ossification.

The secondary centers develop via endochondral ossification:

- The medial epiphysis, where 80% of growth occurs, ossifies at ages 12 to 19 years and fuses by ages 22 to 25 years (last bone to fuse).

- The lateral epiphysis does not ossify until it fuses at age 19 years.

Clavicular range of motion involves rotation about its long axis (approximately 50 degrees) accompanied by elevation of 30 degrees with full shoulder abduction and 35 degrees of anterior–posterior angulation with shoulder protraction and retraction.

The periosteal sleeve always remains in the anatomic position. Therefore, remodeling is ensured.

Mechanism of Injury

Indirect: Fall onto an outstretched hand.

Direct: This is the most common mechanism, resulting from direct trauma to the clavicle or acromion; it carries the highest incidence of injury to the underlying neurovascular and pulmonary structures.

Birth injury: Occurs during delivery of the shoulders through a narrow pelvis with direct pressure from the symphysis pubis or from obstetric pressure directly applied to the clavicle during delivery.

Medial clavicle fractures or dislocations usually represent Salter-Harris type I or II fractures. True sternoclavicular joint dislocations are rare. The inferomedial periosteal sleeve remains intact and provides a scaffold for remodeling. Because 80% of the growth occurs at the medial physis, there is great potential for remodeling.

Lateral clavicle fractures occur as a result of direct trauma to the acromion. The coracoclavicular ligaments always remain intact and are attached to the inferior periosteal tube. The acromioclavicular ligament is always intact and is attached to the distal fragment.

Clinical Evaluation

Birth fractures of the clavicle are usually obvious, with an asymmetric, palpable mass overlying the fractured clavicle. An asymmetric Moro reflex is usually present. Nonobvious injuries may be misdiagnosed as congenital muscular torticollis because the patient will often turn his or her head toward the fracture to relax the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Children with clavicle fractures typically present with a painful, palpable mass along the clavicle. Tenderness is usually discrete over the site of injury, but it may be diffuse in cases of plastic bowing. There may be tenting of the skin, crepitus, and ecchymosis.

Neurovascular status must be carefully evaluated because injuries to the brachial plexus and upper extremity vasculature may occur. Rule out brachial plexus palsy.

Pulmonary status must be assessed, especially if direct trauma is the mechanism of injury. Medial clavicular fractures may be associated with tracheal compression, especially with severe posterior displacement.

Differential diagnosis

- Cleidocranial dysostosis: This defect in intramembranous ossification, most commonly affecting the clavicle, is characterized by absence of the distal end of the clavicle, a central defect, or complete absence of the clavicle. Treatment is symptomatic only.

- Congenital pseudarthrosis: This most commonly occurs at the junction of the middle and distal thirds of the right clavicle, with smooth, pointed bone ends. Pseudarthrosis of the left clavicle is found only in patients with dextrocardia. Patients present with no antecedent history of trauma, only a palpable bump. Treatment is supportive only, with bone grafting and intramedullary fixation reserved for symptomatic cases.

Radiographic Evaluation

Ultrasound evaluation may be used in the diagnosis of clavicular fracture in neonates.

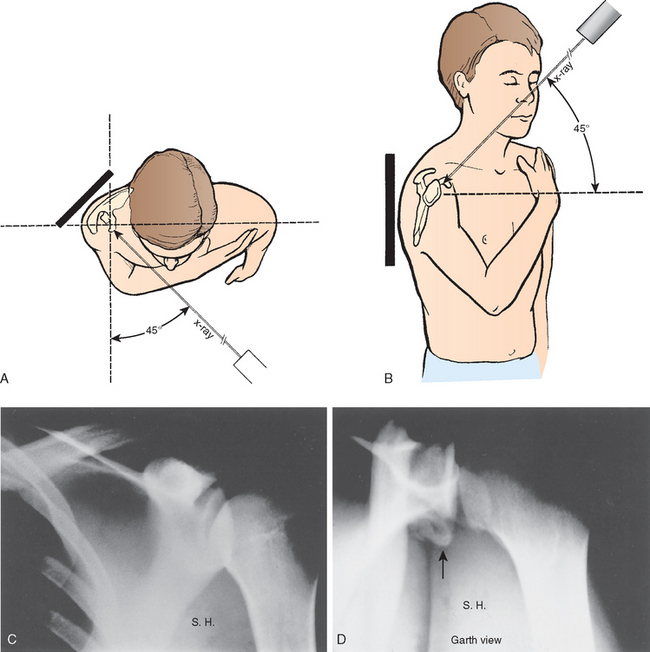

Because of the S-shape of the clavicle, an anteroposterior (AP) view is usually sufficient for diagnostic purposes; however, special views have been described in cases in which a fracture is suspected but not well visualized on a standard AP view:

- Cephalic tilt view (cephalic tilt of 35 to 40 degrees): This minimizes overlapping structures to better show degree of displacement.

- Apical oblique view (injured side rotated 45 degrees toward tube with a cephalic tilt of 20 degrees): This is best for visualizing nondisplaced middle third fractures.

Patients with difficulty breathing should have an AP radiograph of the chest to evaluate possible pneumothorax or associated rib fractures.

Computed tomography may be useful for the evaluation of medial clavicular fractures or suspected dislocation, because most represent Salter-Harris type I or II fractures rather than true dislocations.

Classification

Descriptive

- Location

- Open versus closed

- Displacement

- Angulation

- Fracture type: segmental, comminuted, greenstick, etc.

Allman:

- Type I: Middle third (most common)

- Type II: Distal to the coracoclavicular ligaments (lateral third)

- Type III: Proximal (medial) third

Treatment

Newborn to Age 2 Years

Complete fracture in patients less than 2 years of age is unusual and may be caused by birth injury.

Clavicle fracture in a newborn will unite in approximately 1 week. Reduction is not indicated. Care should be taken when lifting the child. A soft bandage may be used for immobilization.

Infants may be treated symptomatically with a simple sling or figure-of-eight bandage applied for 2 to 3 weeks or until the patient is comfortable. One may also pin the sleeve of a long-sleeved shirt to the contralateral shoulder.

Ages 2 to 12 Years

A figure-of-eight bandage or sling is indicated for 2 to 4 weeks, at which time union is complete.

Age 12 Years to Maturity

The incidence of complete fracture is higher.

A figure-of-eight bandage or sling is used for 3 to 4 weeks. However, figure-of-eight bandages are often poorly tolerated and have been associated with ecchymosis, compression of axillary vessels, and brachial plexopathy.

If the fracture is grossly displaced with tenting of the skin, one should consider closed or open reduction with or without internal fixation.

Open Treatment

Operative treatment is indicated in open fractures and those with neurovascular compromise.

Comminuted fragments that tent the skin may be manipulated and the dermis released from the bone ends with a towel clip. Typically, bony fragments are placed in the periosteal sleeve and the soft tissue repaired. One can also consider internal fixation.

Bony prominences from callus will usually remodel; exostectomy may be performed at a later date if necessary, although from a cosmetic standpoint the surgical scar is often more noticeable than the prominence.

Complications

- Neurovascular compromise: Rare in children because of the thick periosteum that protects the underlying structures, although brachial plexus and vascular injury (subclavian vessels) may occur with severe displacement.

- Malunion: Rare because of the high remodeling potential; it is well tolerated when present, and cosmetic issues of the bony prominence are the only long-term issue.

- Nonunion: Rare (1% to 3%); it is probably associated with a congenital pseudarthrosis; it never occurs <12 years of age.

- Pulmonary injury: Rare injuries to the apical pulmonary parenchyma with pneumothorax may occur, especially with severe, direct trauma in an anterosuperior to posteroinferior direction.

1. What is the most common mechanism of injury for clavicle fractures?

Answer: a. Direct trauma to the clavicle or acromion. This is the most common mechanism of injury, accounting for the majority of clavicle fractures. It also carries the highest incidence of injury to underlying neurovascular and pulmonary structures.

2. What is the most frequent long bone fracture in children?

Answer: c. Clavicle. Clavicle fractures are among the most common fractures in pediatric patients, accounting for 8-15% of all pediatric fractures.

3. At what age does the lateral epiphysis of the clavicle ossify?

Answer: b. Ages 19-22 years. The lateral epiphysis of the clavicle does not ossify until it fuses at age 19 years, which is later than the medial epiphysis.

4. What type of fracture represents 80% of clavicle fractures?

Answer: c. Midshaft fractures. Eighty percent of clavicle fractures occur in the midshaft, most frequently just lateral to the insertion of the subclavius muscle.

5. What is the typical treatment for clavicle fractures in infants?

Answer: c. Observation and immobilization in a soft bandage. Clavicle fractures in infants will unite in approximately 1 week, and reduction is not indicated. Treatment should be focused on immobilization and careful handling of the infant. A soft bandage is typically used for immobilization.