Everything You Need to Know About Pediatric Scapula Fractures

Learn about pediatric scapula fractures, including epidemiology, anatomy, mechanism of injury, clinical evaluation, radiographic evaluation, classification, and treatment, with potential complications.

Pediatric Scapula Fractures

The scapula is relatively protected from trauma by the thoracic cavity and the rib cage anteriorly as well as by the encasing musculature.

Scapular fractures are often associated with other life-threatening injuries that have greater priority.

Epidemiology

These are less common in children than in adults where they constitute only 1% of all fractures and 5% of shoulder fractures in the general population.

Anatomy

The scapula forms from intramembranous ossification. The body and spine are ossified at birth.

The center of the coracoid is ossified at 1 year. The base of the coracoid and the upper one-fourth of the glenoid ossify by 10 years. A third center at the tip of the coracoid ossifies at a variable time. All three structures fuse by age 15 to 16 years.

The acromion fuses by age 22 years via two to five centers, which begin to form at puberty.

Centers for the vertebral border and inferior angle appear at puberty and fuse by age 22 years. The center for the lower three-fourths of the glenoid appears at puberty and fuses by age 22 years.

The suprascapular nerve traverses the suprascapular notch on the superior aspect of the scapula, medial to the base of the coracoid process, thus rendering it vulnerable when fractures occur in this region.

The superior shoulder suspensory complex (SSSC) is a circular group of both bony and ligamentous attachments (acromion, glenoid, coracoid, coracoclavicular ligament, and distal clavicle). The integrity of the ring is breached only after more than one violation. This can dictate the treatment approach.

Mechanism of Injury

In children, most scapula fractures represent avulsion fractures associated with glenohumeral joint injuries. Other fractures are usually the result of high-energy trauma.

Isolated scapula fractures are extremely uncommon, particularly in children; child abuse should be suspected unless a clear and consistent mechanism of injury exists.

The presence of a scapula fracture should raise suspicion of associated injuries because 35% to 98% of scapula fractures occur in the presence of other injuries, including:

- Ipsilateral upper torso injuries: fractured ribs, clavicle, sternum, shoulder trauma

- Pneumothorax: seen in 11% to 55% of scapular fractures

- Pulmonary contusion: present in 11% to 54% of scapula fractures

- Injuries to neurovascular structures: brachial plexus injuries, vascular avulsions

- Spinal column injuries: 20% lower cervical spine, 76% thoracic spine, 4% lumbar spine

- Others: concomitant skull fractures, blunt abdominal trauma, pelvic fracture, and lower extremity injuries, which are all seen with higher incidences in the presence of a scapula fracture

Rate of mortality in setting of scapula fractures may approach 14%.

Clinical Evaluation

Full trauma evaluation, with attention to airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and exposure should be performed, if indicated.

Patients typically present with the upper extremity supported by the contralateral hand in an adducted and immobile position, with painful range of shoulder motion, especially with abduction.

A careful examination should be performed to evaluate for associated injuries with a comprehensive assessment of neurovascular status and an evaluation of breath sounds.

Radiographic Evaluation

Initial radiographs should include a trauma series of the shoulder, consisting of true AP, axillary, and scapular-Y (true scapular lateral) views; these generally are able to demonstrate most glenoid, neck, body, and acromion fractures.

The axillary view may be used to further delineate acromial and glenoid rim fractures.

An acromial fracture should not be confused with an os acromiale, which is a rounded, unfused apophysis at the epiphyseal level and is present in approximately 3% of the population. When present, it is bilateral in 60% of cases. The os is typically in the anteroinferior aspect of distal acromion.

Glenoid hypoplasia, or scapular neck dysplasia, is an unusual abnormality that may resemble glenoid impaction and may be associated with humeral head or acromial abnormalities. It has a benign course and is usually noted incidentally.

A 45-degree cephalic tilt (Stryker notch) radiograph is helpful to identify coracoid fractures.

Computed tomography may be useful for further characterizing intra-articular glenoid fractures.

Because of the high incidence of associated injuries, especially to thoracic structures, a chest radiograph is an essential part of the evaluation.

Classification

Classification by Location

- Body (35%) and Neck (27%) Fractures

- Isolated versus associated disruption of the clavicle

- Displaced versus nondisplaced

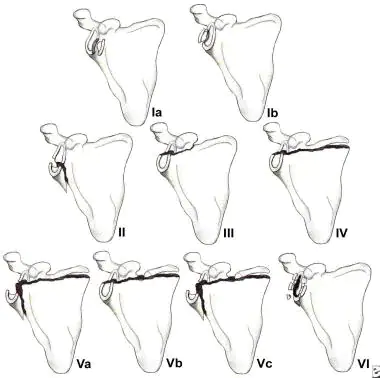

- Glenoid Fractures (Ideberg and Goss)

- IA: Anterior avulsion fracture

- IB: Posterior rim avulsion

- II: Transverse with inferior free fragment

- III: Upper third including coracoid

- IV Horizontal fracture extending through body

- V: Combined II, III, and IV

- VI: Extensively comminuted

Treatment

Scapula body fractures in children are treated nonoperatively, with the surrounding musculature maintaining reasonable proximity of fracture fragments. Operative treatment is indicated for fractures that fail to unite, which may benefit from partial body excision.

Scapula neck fractures that are nondisplaced and not associated with clavicle fractures may be treated nonoperatively. Significantly displaced fractures may be treated in a thoracobrachial cast. Associated clavicular disruption, either by fracture or ligamentous instability (i.e., multiple disruptions in the SSSC), is generally treated operatively with open reduction and internal fixation of the clavicle alone or open reduction and internal fixation of the scapula fracture through a separate incision.

Coracoid fractures that are nondisplaced may be treated with sling immobilization. Displaced fractures are usually accompanied by acromioclavicular dislocation or lateral clavicular injury and should be treated with open reduction and internal fixation.

Acromial fractures that are nondisplaced may be treated with sling immobilization. Displaced acromial fractures with associated subacromial impingement should be reduced and stabilized with screw or plate fixation.

Glenoid fractures in children, if not associated with glenohumeral instability, are rarely symptomatic when healed and can generally be treated nonoperatively if they are nondisplaced.

- Type I: Fractures involving greater than one-fourth of the glenoid fossa that result in instability may be amenable to open reduction and lag screw fixation.

- Type II: Inferior subluxation of the humeral head may result, necessitating open reduction, especially when associated with a greater than 5-mm articular step-off. An anterior approach usually provides adequate exposure.

- Type III: Reduction may be difficult; fractures occur through the junction between the ossification centers of the glenoid and are often accompanied by a fractured acromion or clavicle, or an acromioclavicular separation. Open reduction and internal fixation followed by early range of motion are indicated.

- Types IV to VI: These are difficult to reduce, with little bone stock for adequate fixation in pediatric patients. A posterior approach is generally utilized for open reduction and internal fixation with Kirschner wire, plate, suture, or screw fixation for displaced fractures.

Complications

- Posttraumatic osteoarthritis: This may result from a failure to restore articular congruity.

- Associated injuries: These account for most serious complications because of the high-energy nature of these injuries.

- Decreased shoulder motion: Secondary to subacromial impingement from acromial fracture.

- Malunion: Fractures of the scapula body generally unite with nonoperative treatment; when malunion occurs, it is generally well tolerated but may result in painful scapulothoracic crepitus.

- Nonunion: Extremely rare, but when present and symptomatic, it may require open reduction and plate fixation for adequate relief.

- Suprascapular nerve injury: May occur in association with scapula body, scapula neck, or coracoid fractures that involve the suprascapular notch.

1. What is the incidence of scapula fractures in children compared to adults?

Answer: a) 1% in children and 5% in adults. Scapula fractures are less common in children than in adults, where they constitute only 1% of all fractures and 5% of shoulder fractures in the general population.

2. What are the common associated injuries with scapula fractures?

Answer: d) All of the above. Associated injuries with scapula fractures include fractured ribs, clavicle, sternum, shoulder trauma, pneumothorax, pulmonary contusion, injuries to neurovascular structures, spinal column injuries, concomitant skull fractures, blunt abdominal trauma, pelvic fracture, and lower extremity injuries.

3. What is the treatment for scapula body fractures in children?

Answer: c) Nonoperative treatment. Scapula body fractures in children are treated nonoperatively, with the surrounding musculature maintaining reasonable proximity of fracture fragments.

4. What may result from a failure to restore articular congruity?

Answer: a) Posttraumatic osteoarthritis. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis may result from a failure to restore articular congruity in scapula fractures.

5. Which type of glenoid fracture may result in inferior subluxation of the humeral head?

Answer: b) Type II. Inferior subluxation of the humeral head may result in Type II glenoid fractures, necessitating open reduction, especially when associated with a greater than 5-mm articular step-off.