Fractured Neck Of Femur

Introduction

A fractured neck of femur (NOF) is a very common orthopaedic presentation.

Over 65,000 hip fractures each year are recorded in the UK and they are becoming increasingly frequent due to an aging population.

The mortality of a femoral neck fracture up to 30% at one year; consequently, these fractures require specialist care and, indeed, most orthopaedic units now have dedicated orthogeriatricians who specialise in the care of this vulnerable patient group.

Neck of femur fractures are typically caused either by low energy injuries (the most common type), such as a fall in frail older patient, or high energy injuries, such as a road traffic collision or fall from height and are often associated with other significant injuries.

In this article, we will look at the classification, anatomy, clinical and radiological features, and management of neck of femur fractures.

Anatomy

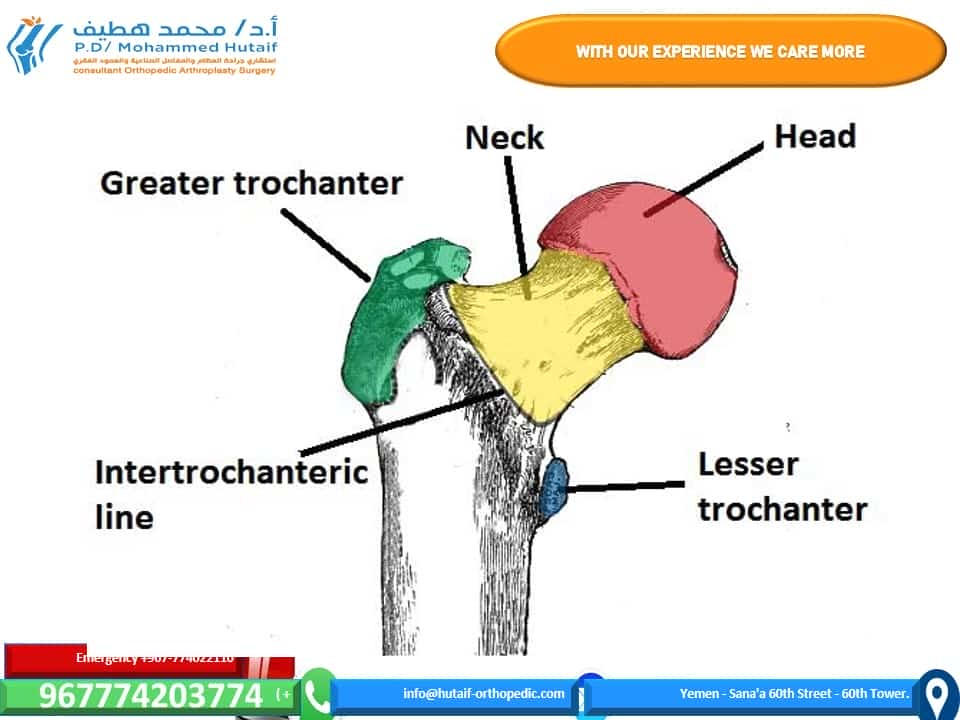

Neck of femur (NOF) fractures can occur anywhere from the subcapital region of the femoral head to 5cm distal to the lesser trochanter (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 – The bony landmarks of the anterior proximal femur

The neck of femur can be considered to have two distinct areas, which are described relative to the joint capsule:

- Intra-capsular – from the subcapital region of the femoral head to basocervical region of the femoral neck, immediately proximal to the trochanters

-

Extra-capsular – outside the capsule, subdivided into:

- Inter-trochanteric, which are between the greater trochanter and the lesser trochanter

- Sub-tronchanteric, which are from the lesser trochanter to 5cm distal to this point

The blood supply to the neck of the femur is retrograde*, passing from distal to proximal along the femoral neck to the femoral head. This is predominantly through the medial circumflex femoral artery, which lies directly on the intra-capsular femoral neck.

Consequently, displaced intra-capsular fractures disrupt the blood supply to the femoral head and, therefore, the femoral head will undergo avascular necrosis (even if the hip is fixed). Patients with a displaced intra-capsular fracture therefore require joint replacement (arthroplasty), rather than fixation.

Intracapsular fractures can also be further classified by the Garden Classification (Table 1)

|

Garden Classification |

Simplified Classification |

Description |

|

I |

Non-displaced |

Incomplete |

|

II |

Complete fracture but nondisplaced |

|

|

III |

Displaced |

Complete fracture, partial displacement |

|

IV |

Complete fracture fully displaced |

Table 1 – The Garden Classification for Intracapsular Hip Fracture

*There is supply in the early days of life from the ligamentum arteriosum, which lies within the ligamentum teres, however this dramatically reduces in size in later life, and is of negligible importance in adults

Clinical Features

The leading symptom is trauma, often low-energy, which is followed by pain and an inability to weight bear. Pain is felt predominantly in the groin, thigh or, commonly in the elderly, referred to the knee.

On examination, the leg is characteristically shortened and externally rotated, due to the pull of the short external rotators (Fig. 2), with pain on pin-rolling the leg and axial loading.

Fortunately, distal neurovascular deficits are rare in isolated neck of femur fractures. However, a full neurovascular examination of the limb is essential, with any deficits urgently acted on.

It is essential that you remember to investigate the cause of their fall, especially if there is not a clear history of a trip or slip.

Figure 2 – Externally rotated and shortened right lower limb

Differential Diagnoses

Alternative fractures, such as of the pelvis (especially pubic ramus fractures), acetabulum, femoral head and femoral diaphysis, all need to be considered. Pathological fractures should be considered if there is not a significant history of trauma.

Investigations

Initial plain-film radiographic imaging should include antero-posterior (AP) and lateral views of the affected hip, as well as an AP pelvis (useful to assess the contralateral normal hip for pre-operative planning and templating)*. Obtain full length femoral radiographs too, if there is suspicion of a pathological fracture.

Basic routine blood tests, including FBC, U&Es, and coagulation screen, are required alongside a Group and Save; if a long lie time could have occurred, a creatinine kinase (CK) level would be recommended to assess for any significant rhabdomyolysis.

A urine dip, chest radiograph (CXR), and ECG are all useful in complete assessment of the older patient group, especially for pre-operative assessment and peri-operative management. As mentioned, further work-up as to the cause of the fall is also essential.

*If there remains clinical equipoise about the diagnosis, repeat plain films whilst manually applying traction to the affected leg or (more commonly) a CT hip may be warranted.

Figure 3 – Pelvic radiograph showing (A) R intracapsular hip fracture (B) L extracapsular hip fracture

Management

Initial management of a neck of femur fracture should consist of an A to E approach to stabilise the patient and treat any immediately life- or limb- threatening problems, as this cohort of patients will likely sustain concurrent injuries (even in low-impact cases).

Ensure adequate analgesia is provided, as hip fractures are very painful. This can be either as opioid analgesia and / or regional analgesia (such as a fascia-iliaca block)

Definitive management is surgical (Table 1), however the specific procedures depending on the type of fracture sustained, amongst several other factors

|

Fracture Type |

Surgical Option |

Summary |

|

Displaced subcapital |

Hip Hemiarthroplasty* |

Replacement of the femoral head and neck via a femoral component fixed in the proximal femur |

|

Inter-trochanteric and Basocervical* |

Dynamic Hip Screw (or short IM nail) |

Consists of a lag screw into the neck, a sideplate, and bicortical screws. The lag screw is able to slide through the sideplate, allowing for compression and primary healing of the bone |

|

Non-displaced intra-capsular |

Cannulated hip screws** |

Three parallel screws in an inverted triangle formation |

|

Sub-trochanteric |

Anterograde Intramedullary Femoral Nail |

The titanium rod is placed through the medullary cavity of the femur for stabilisation |

Table 2 – Summary of Surgical Options for NOF Fractures; *consider total hip arthroplasty in systemically well patient who was living independently prior to injury; **can also consider hip hemiarthoplasty or total hip arthroplasty

Non-operative conservative management is rarely recommended, as the benefits of surgical intervention nearly always outweigh the potential conservative management.

Immediate post-operative complications include pain, bleeding, leg-length discrepancies, and potential neurovascular damage, all of which should be consented for pre-operatively.

Post-operatively, NOF patients should be managed jointly under the care of the ortho-geriatricians, so ensuring that the patients are optimally cared for. Best outcomes are achieved with early rehabilitation, through engagement with physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

Figure 4 – A hip radiograph demonstrating cannulated hip screws in-situ

Complications

Long term complications following repair include joint dislocation, aseptic loosening, peri-prosthetic fracture, and deep infection/prosthetic joint infection. The mortality following a femoral neck fracture is up to 30% at one year.

Key Points

- Neck of femur fractures are associated with a high one year mortality and the patient cohort are often elderly with multiple co-morbidities

- They will present as an acutely painful hip that is shortened and externally rotated

- Treatment of neck of femur fracture is primarily surgical, the specific procedure required will depend on the classification of the fracture

- Ensure early assessment by ortho-geriatricians alongside physiotherapists and occupational therapists