Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of the Symphysis

DEFINITION

■The pubic symphysis comprises a fibrocartilaginous disc between the bodies of the two pubic bones.

■A diastasis of the pubic symphysis indicates a disruption of the pelvic ring and an unstable pelvis.

■The symphysis is disrupted in anterior–posterior compression (APC) injuries as classified by Young and Burgess and occasionally in lateral compression fractures.

ANATOMY

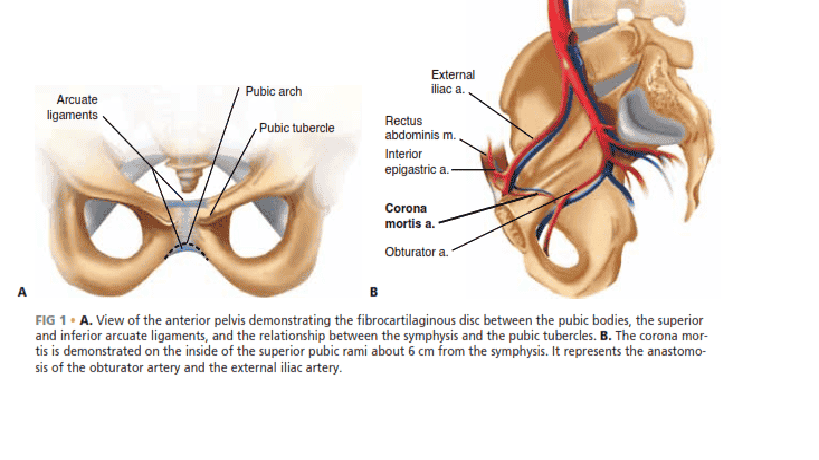

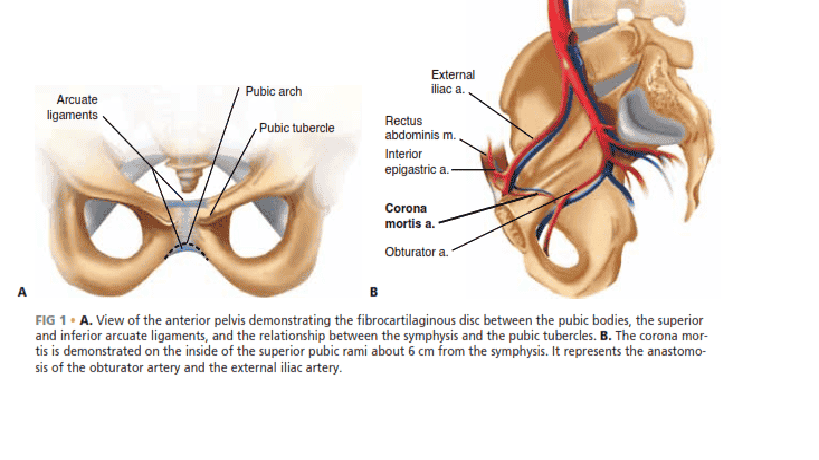

■The symphysis is an amphiarthrodial joint, consisting of a fibrocartilaginous disc, and stabilized by the superior and inferior arcuate ligaments (FIG 1A).

■The corona mortis is a vessel that represents the anastomosis between the obturator artery and the external iliac artery. It is located about 6 cm laterally on either side of the symphysis (FIG 1B).14

■Lateral to the symphysis on the superior rami is the pubic tubercle, a prominence representing the attachment of the inguinal ligament.

■This bony landmark must be accounted for when contouring a plate that is going to span the symphysis.

■Anatomic variation exists between the sexes, with females having a wider and more rounded pelvis, making their anterior pelvic ring more concave than males (FIG 2).

■The pelvic arch formed by the convergence of the inferior rami tends to be more rounded in females because their pubic bodies are shallower than males.

■The arcuate ligaments are the main soft tissue stabilizers of the anterior pelvis.

■These ligaments arc both superiorly and inferiorly and are firmly attached to the pubic rami.

■The sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments play an important role in the stability of pelvic fractures. These ligaments connect the sacrum to the ilium via the ischial spine and the ischial tuberosity. The sacrospinous ligament resists the rotational forces of the hemipelvis, and the sacrotuberous ligament prevents rotation as well as translation of the hemipelvis.13

■If these ligaments and the pelvic floor are torn in conjunction with a pelvic fracture, symphyseal widening is more significant .4

PATHOGENESIS

■The Young and Burgess classification describes the injury by the type of force acting on the pelvis. Symphyseal diastasis is most commonly seen in APC injuries or open book pelvis injuries.

■In APC injuries minor widening of the symphysis may not involve disruption of the pelvic floor, including the sacrospinous ligaments.

■In cadaver pelvi, where the symphysis and sacrospinous ligaments were sectioned, more than 2.5 cm of symphyseal widening was observed, thus defining a rotationally unstable pelvis.12

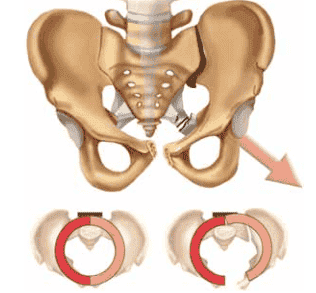

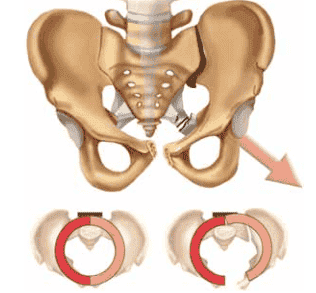

■If the pelvic floor and the sacrospinous ligaments are torn, the involved hemipelvis can externally rotate down and out,

FIG 1 • A. View of the anterior pelvis demonstrating the fibrocartilaginous disc between the pubic bodies, the superior and inferior arcuate ligaments, and the relationship between the symphysis and the pubic tubercles. B. The corona mortis is demonstrated on the inside of the superior pubic rami about 6 cm from the symphysis. It represents the anastomosis of the obturator artery and the external iliac artery.

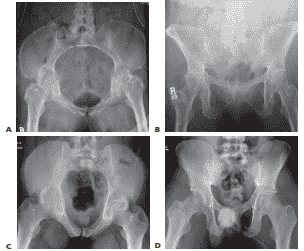

FIG 2 • Examples of the anatomic variants between genders. The female pelvis has a more concave shape to the ring and the pubic arch has less of an acute angle because of the broader pubic body, as demonstrated in the inlet (A) and outlet (B) views of a female pelvis. The male pelvic ring is more oval, with a much more acute angle anteriorly because of the thinner pubic body, as seen the corresponding inlet (C) and outlet (D) views. rotating on the intact posterior sacroiliac ligaments and creating an unstable pelvis (FIG 3).4

■Occasionally, lateral compression (LC) injuries involve fractures of the pubic rami and a symphyseal disruption. This occurs when the compressed hemipelvis causes the contralateral rami to fracture and the contralateral symphyseal body to tilt inferiorly. Because one side of the symphysis is off and can

FIG 3 • The hemipelvis externally rotates out when the posterior sacroiliac ligaments remain intact, as in an anterior–posterior compression type II injury. The posterior ligaments act as a hinge, and with sacrospinous ligaments torn the involved hemipelvis will rotate down and out, so the pubic body on the injured side will be below the intact pubic body. compress the bladder or uterus, altering the pelvic ring, it should be reduced to the other pubic body, which remains intact.

FIG 3 • The hemipelvis externally rotates out when the posterior sacroiliac ligaments remain intact, as in an anterior–posterior compression type II injury. The posterior ligaments act as a hinge, and with sacrospinous ligaments torn the involved hemipelvis will rotate down and out, so the pubic body on the injured side will be below the intact pubic body. compress the bladder or uterus, altering the pelvic ring, it should be reduced to the other pubic body, which remains intact.

■These are referred to as tilt fractures, and open reduction and internal fixation should be considered to prevent impingement of the birth canal and bladder.13

■A diastasis of the pubic symphysis can also occur in pregnancy and during childbirth because of hormonally induced ligamentous laxity. This can lead to chronic instability, and stabilization of the symphysis has been shown to relieve painful symptoms.16

NATURAL HISTORY

■Persistent low back pain, anterior pain, sitting imbalance, and an impaired, painful gait are common sequelae after pelvic fractures.

■Early studies looking at pelvic fractures without surgical treatment demonstrated that almost a third of these patients had disabling pain and impaired gait. Only a third had no symptoms if the posterior ring was involved.16

■APC type I injuries are Tile type A stable pelvic injuries, which do well with nonoperative treatment. These injuries tend to occur in younger patients involved in motor vehicle trauma or in elderly patients as a result of a direct injury such as a fall.

■ APC type II and III injuries are unstable injuries. Nonoperative treatment has resulted in late pain in these injuries. In a retrospective study by Tile, APC type II injuries treated nonoperatively had a 13% incidence of late pain, with the majority of patients reporting persistent moderate pain. The patients with APC type III injuries reported a 16% incidence of late pain, with most pain being reported as moderate or severe.13

■Patients with pelvic trauma tend to have other organ systems involved, and these associated injuries contribute to longterm disability. The more severe injuries associated with pelvic fractures are urologic and neurologic injuries.16

■Whitbeck et al demonstrated higher morbidity and mortality rates as well as an increased incidence of arterial injuries in APC type III injuries compared to other pelvic fractures.18

■Disruption of the pubic symphysis is associated with urologic injuries. Bladder ruptures and urethral tears occur about 15% of the time in association with pelvic trauma and can lead to late complications such as strictures and incontinence. These associated injuries potentially lead to a higher infection rate when open reduction and internal fixation is performed.8 An increased incidence of incontinence has also been seen in women with APC injuries.

■Neurologic injuries associated with pelvic fractures occur when there is posterior pathology and are more common with sacral fractures and vertically unstable fracture patterns.

■Dyspareunia and sexual dysfunction are also described as complications after pelvic fractures.7 They can occur directly from the injury or as a result of ectopic bone formation during healing.

■Symphyseal pelvic dysfunction, a relatively common condition, presents as anterior pelvic pain secondary to the laxity in the symphysis. This condition typically resolves spontaneously and can take some time but needs to be differentiated from traumatic symphyseal diastasis as a result of childbirth. Traumatic diastasis occurs in about 1 in 2000 births to 1 in 30,000 births, and the diastases from pregnancy can be as great as 12 cm.3

■Most patients with postpartum displacement recover with no residual pain or instability after treatment with pelvic binders, girdles, and the recommendation to lie in the lateral decubitus position.

■There are a limited number of studies looking at symphyseal disruption secondary to pregnancy. The exact incidence of persistent long-term pain is unknown, but chronic pelvic instability can occur if it is unrecognized.9

■In the few series reporting operative treatment, the indication was persistent pain for at least 4 to 6 months postpartum.3,9

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■Pelvic injuries usually occur as a result of any high-energy trauma, such as high-speed motor vehicle accidents, motorcycle accidents, or falls from heights.

■Patients with pelvic fractures may become hemodynamically unstable, and close monitoring of blood pressure and fluid requirements is needed.

■Typically, if a patient requires more than 4 units of blood to maintain hemodynamic stability, an angiogram should be obtained to diagnose and embolize any arterial injuries. Clotting factors and platelets should also be administered.

■Patients may have tenderness to palpation in the area of the symphysis. If motion of the pelvis is detected, manipulation of the pelvis should cease, as unnecessary manipulation may disturb any clot formation (see Exam Table for Pelvis and Lower Extremity Trauma, pages 1 and 2).

■If there is no radiographic demonstration of displacement, the iliac wings can be compressed to test for stability of the pelvic ring and each hemipelvis.

■A careful examination of the skin to identify areas of ecchymosis and hematoma formation, particularly in the flanks, groin, and abdominal regions, also needs to be performed.

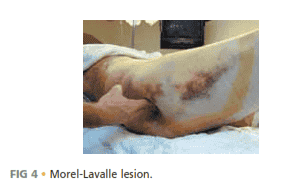

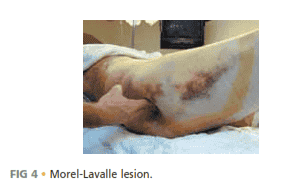

■The presence of a Morel-Lavalle lesion indicates that highenergy trauma has occurred in the pelvic region

(FIG 4). Recognition of this lesion is important to prevent infection.

■A good pelvic examination and evaluation of the perineum are essential. Swelling or open wounds in the perineal area may indicate a high-energy mechanism of injury. Open injuries require emergent management.

FIG 4 • Morel-Lavalle lesion.

■Evaluation of other organ systems, looking for associated injuries, is essential.

■In males, a high-riding prostate on the rectal examination or blood at the meatus may indicate injury to the urethra or bladder, and placement of a Foley catheter should be delayed until a retrograde urethrogram is performed, unless the patient is in extremis.

■Urethral injuries are less common in females because the urethra is shorter.

■A thorough neurologic examination of the lower extremities also needs to be performed, as injuries to the L4 and L5 nerve roots can occur in pelvic fractures. It is essential to test the sensation and motor functions of specific roots, identifying any neurologic injury that can differentiate between a nerve root lesion or a more central lesion.

■A limb-length discrepancy or a rotational deformity of the lower extremities should prompt radiographic evaluation of the pelvis.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

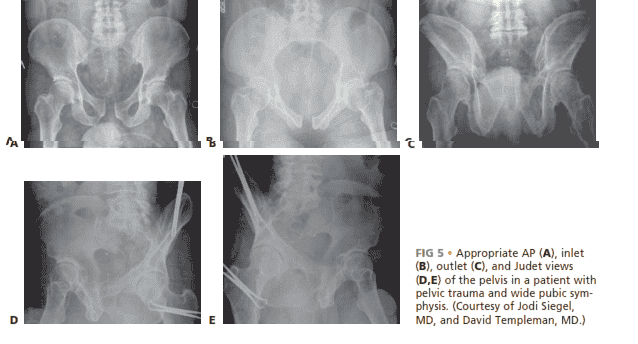

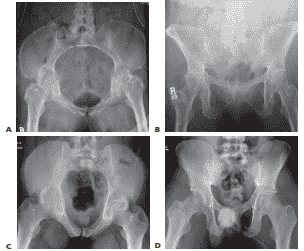

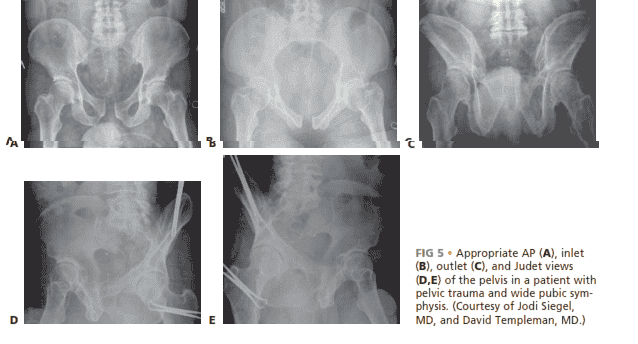

■Radiographic evaluation of the pelvis consists of anteroposterior (AP), inlet, outlet, and Judet views (FIG 5).

■A retrograde urethrogram and sometimes a CT cystogram should be performed to rule out an injury to the genitourinary system in men. A CT cystogram is sufficient for females.

■A CT scan of the pelvis is also indicated to help evaluate intra-articular injuries to the sacroiliac joints and further delineate the fracture pattern.

■A CT angiogram can also be used at the time of the trauma scan to help predict if an arterial bleed is present and requires further treatment with angiography and embolization.10

■Angiography may be used to treat patients who are hemodynamically unstable and do not respond to standard resuscitation, particularly if a CT angiogram indicates arterial bleeding.

■A stress examination in the operating room can be performed under fluoroscopy to assess stability if there is a question of an unstable pelvis.

■Single-leg stance views can also be performed if it is not clear whether an injury is unstable. This is a good examination for evaluating patients who may have chronic instability, such as a female patient with ligamentous laxity secondary to pregnancy or unrecognized pelvic injury.9,14

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

■Rami fractures

■Symphyseal strain

■Hip fracture

■Muscle strain or avulsion

■Lumbar fracture

FIG 5 • Appropriate AP (A), inlet (B), outlet (C), and Judet views (D,E) of the pelvis in a patient with pelvic trauma and wide pubic symphysis. )

ACUTE MANAGEMENT

■The patients should be hemodynamically stabilized.

■The pelvis can be stabilized by placing ankles together with Ace wraps. Heels and ankles should be padded to prevent skin breakdown and ulcer formation.

■Placing a sheet across the pelvis at the level of the greater trochanters can be used to reduce the symphysis and temporarily stabilize the pelvis. The sheet can be affixed with towel clips to hold it with tension rather than tying a knot across the abdomen .

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

■If minimal separation of the symphysis is present, the patient can be made non-weight bearing on the affected side and can be allowed to ambulate.

■Close radiographic monitoring should ensue, with weekly radiographs. Single-leg stance views can be used to help identify late instability.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

■A diastasis larger than 2.5 mm indicates a disruption of the sacrospinous ligaments and thus an unstable pelvis. Open fixation of the symphysis stabilizes the anterior pelvis.2

■Open injuries can be stabilized with external fixation, using iliac wing pins or Hanover pins placed at the level of the anterior inferior iliac spine.

■In APC type II injuries with an intact hemipelvis, no posterior fixation is needed, and the symphysis is reduced and stabilized first.

■For type III injuries, if the innominate bone is broken, the anterior pelvic ring is reduced and fixed after the posterior ring is reduced and fixed. The anterior pelvic ring is reduced and fixed as a first step if the innominate bone remains intact.

■Indications for anterior stabilization for vertically unstable pelvic fractures include improving anterior stability to the pelvic ring, stabilizing a pelvic injury that is associated with an injury requiring a laparotomy, treatment of bone protruding into the perineum (ie, a tilt fracture), or in association with an acetabular fracture requiring open reduction.13

Preoperative Planning

■The surgeon should review appropriate radiographic studies (AP, inlet, and outlet views and CT scan).

■Identifying all rami fractures and the presence of any pubic body fractures is essential, as this will help determine how to obtain a reduction as well as dictate the type of fixation necessary.

■The surgeon should plan to obtain stress views in the operating room to determine the stability of the pelvis if there is any question of stability.

■The surgeon should rule out the presence of a bladder rupture or urethral tear. If one is present, repair should be performed at the same time as internal fixation of the symphysis if possible to avoid a more complex late reconstruction.

■Any history of previous abdominal surgery or the presence of prior incisions should be identified before going to the operating room.

■The proper equipment must be available, such as C-arm, radiolucent table, large bone clamps, external fixation equipment, and a C-clamp. Positioning

■The patient is placed on a radiolucent flat-top table with legs together to facilitate reduction of the symphysis.

■Fluoroscopic radiographs confirming the ability to obtain a good inlet and outlet views with the C-arm are obtained before preparing and draping the patient.

■Right-handed surgeons may prefer to have the C-arm on the patient’s right side and the drill and instruments on the patient’s left for easier access to the symphysis with the drill.

■Placement of a Foley catheter is needed to decompress the bladder; it can also be felt intraoperatively to help identify the bladder.

■Venodyne boots are placed on both legs if possible for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis during the case. Approach

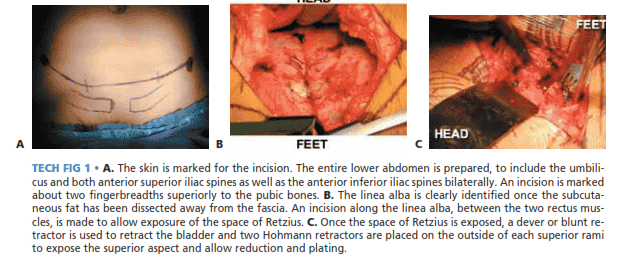

■Open reduction of the symphysis is performed with an anterior Pfannenstiel approach.

PFANNENSTIEL APPROACH

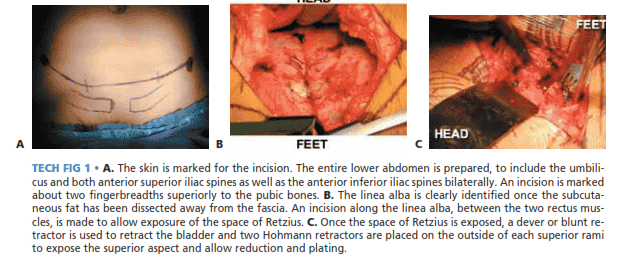

■The entire lower abdomen is prepared, including both anterior superior iliac spines, the symphysis, and the umbilicus.

■ Access to the anterior superior iliac spines is important if an external fixator is to be placed to assist in reduction or for additional fixation.

■A transverse incision is made 2 cm above the symphysis (TECH FIG 1A).

■Once through the skin, a large rake is placed to help create a plane above the rectus fascia.

■A longitudinal incision is then made along the fascia of the linea alba. The rectus muscle insertion is not taken down, although it is common to see an avulsion of one of the rectus muscles off the rami from the initial injury (TECH FIG 1B).

■Blunt dissection is continued longitudinally to spread the rectus muscle and protect the underlying peritoneum and bladder.

■ Electric cautery can be used to divide the remaining fibers of the rectus while protecting the underlying structures.

■The bladder and bladder neck are evaluated for the presence of any injury.

■At this point, a blunt malleable retractor can be placed into the space of Retzius to protect the bladder (TECH FIG 1C).

■Care should be taken laterally, as the vessels known as the corona mortis tend to be about 6 cm lateral to the symphysis.

■ The corona mortis is an anastomosis of the obturator and external iliac arteries (see Fig 1B).14

■Hohmann retractors are placed through the periosteum superiorly over the superior pubic rami one side at a time to retract the rectus muscle laterally and expose the superior body of the symphysis.

■ These retractors are placed close to the external iliac vessels, so they need to be placed with care directly onto bone.

■The periosteum on the superior aspect of the rami can now be stripped off with an electric cautery and osteotomes.

■Some surgeons remove the symphyseal cartilage to promote fusion, and we agree with this approach. A

TECH FIG 1 • A. The skin is marked for the incision. The entire lower abdomen is prepared, to include the umbilicus and both anterior superior iliac spines as well as the anterior inferior iliac spines bilaterally. An incision is marked about two fingerbreadths superiorly to the pubic bones. B. The linea alba is clearly identified once the subcutaneous fat has been dissected away from the fascia. An incision along the linea alba, between the two rectus muscles, is made to allow exposure of the space of Retzius. C. Once the space of Retzius is exposed, a dever or blunt retractor is used to retract the bladder and two Hohmann retractors are placed on the outside of each superior rami to expose the superior aspect and allow reduction and plating.

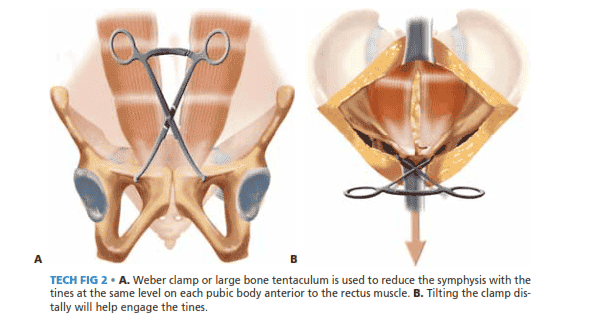

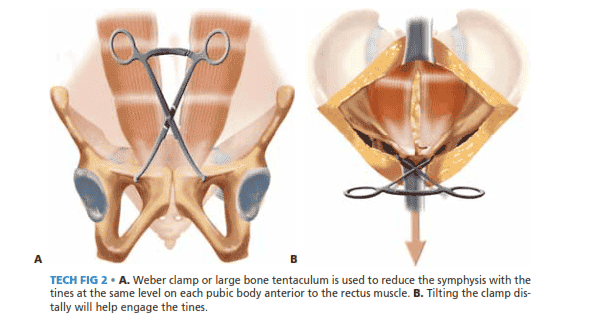

WEBER CLAMP REDUCTION

■Once the superior aspect of the symphyseal bodies is exposed, the Weber clamp is placed anteriorly to avoid removing the insertion of the rectus (TECH FIG 2A).

■The goal in using this technique is to have the tips of the Weber clamp at the same level on each symphyseal body.

■If anterior displacement is present on either side, the tip of the clamp is placed slightly anterior on that side so at the time of reduction the tips are at the same level.4

■The clamp is tilted distally to engage the tines (TECH FIG 2B).

■The clamp is placed anterior to the rectus insertions.

TECH FIG 2 • A. Weber clamp or large bone tentaculum is used to reduce the symphysis with the tines at the same level on each pubic body anterior to the rectus muscle. B. Tilting the clamp distally will help engage the tines.

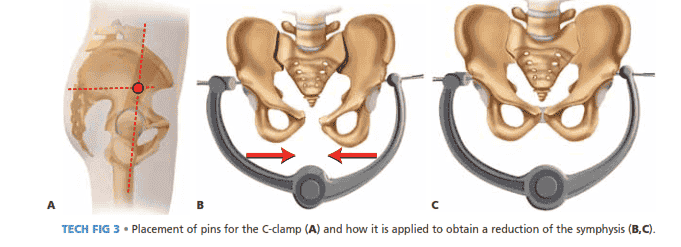

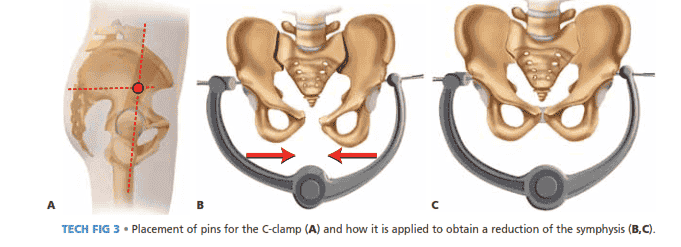

USE OF A C-CLAMP TO AID IN REDUCTION

■The C-clamp has been described for use in unstable APC pelvic fractures in patients requiring an exploratory laparotomy or as temporary pelvic fixation if the patient cannot go to the operating room. It can also be used to assist in the open reduction of the symphysis if conventional clamps cannot hold the reduction.

■This is a similar concept to the one described by Wright et al for assisting in the reduction of the posterior pelvic ring.17

■To apply the C-clamp, the pins are placed two fingerbreadths directly posterior to the anterior superior iliac spine. This places the pins in the gluteus pillar, a thickened portion of the lateral ilium above the acetabulum (TECH FIG 3A).

■Once the pins are in place, the clamp can be fitted onto the pins. The clamp is then used to compress the pelvis and reduce the rotationally unstable hemipelvis (TECH FIG 3B,C). Once reduced, the clamp is tightened and locked down. Fluoroscopy is used to confirm reduction of the symphysis as well as any posterior pathology. (See Chap. TR-1 for further description of the C-clamp.)

■Care should be taken not to overreduce rami fractures if they are present.

■The goal of this technique is to obtain most of the reduction and then fine-tune the reduction once the symphysis is exposed in the usual manner with the Weber clamp.

TECH FIG 3 • Placement of pins for the C-clamp (A) and how it is applied to obtain a reduction of the symphysis (B,C). 482 Part 2 PELVIS AND LOWER EXTREMITY TRAUMA • Section I

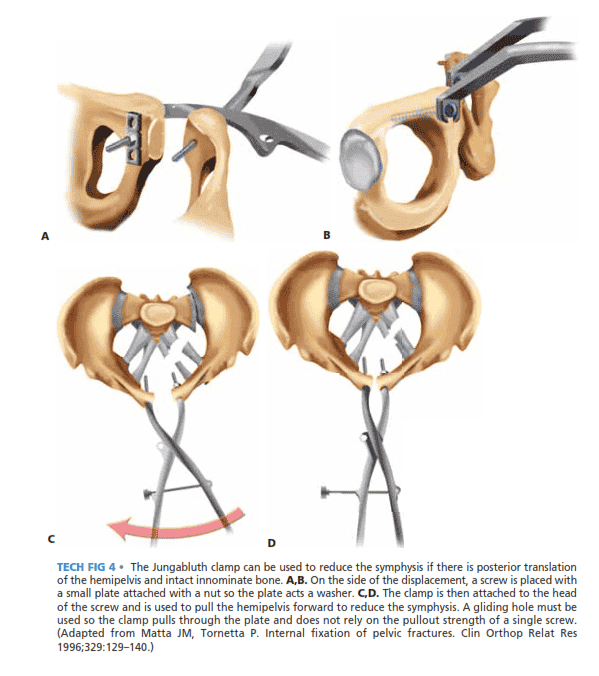

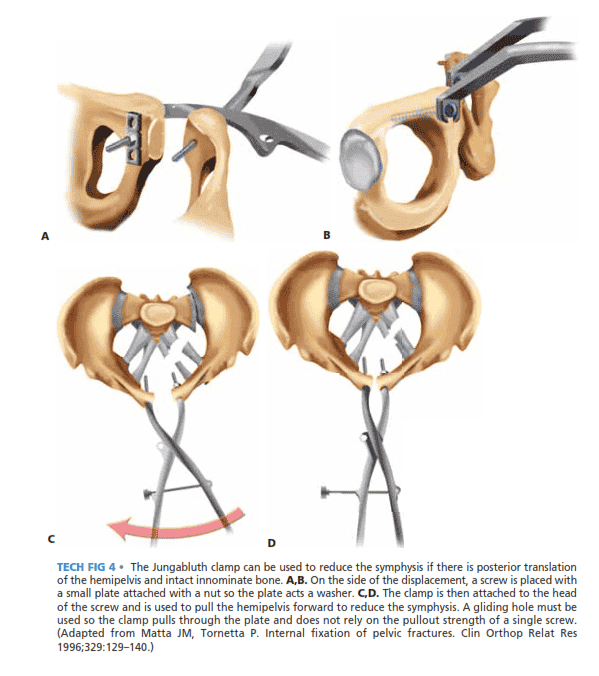

PELVIS AND HIP JUNGABLUTH CLAMP REDUCTION (TECHNIQUE OF MATTA)

■Jungabluth clamp reduction is used when the innominate bone is intact and the posterior ring is unstable.

■The innominate bone tends to be externally rotated, posteriorly displaced, and superiorly translated. If this is the case or vertical instability exists, the entire innominate bone needs to be manipulated to obtain a reduction.

■ In these cases, the use of the Jungabluth clamp may be necessary to achieve reduction.

■Drill holes are made in an anterior-to-posterior direction for the placement for 4.5-mm screws.

■For the screw being placed on the unstable side (with posterior displacement), a 4.5-mm gliding hole is drilled and the screw is secured to the bone through a small plate on the posterior side of the pubis using a nut (TECH FIG 4A,B).

■ The plate will act as a washer and provides a larger surface area of force to be exerted on the hemipelvis so one does not have to rely on the pullout strength of a single screw.

■The Jungabluth clamp is then placed anteriorly and secured to the 4.5-mm screws and can then be used to achieve the reduction (TECH FIG 4C,D).

TECH FIG 4 • The Jungabluth clamp can be used to reduce the symphysis if there is posterior translation of the hemipelvis and intact innominate bone. A,B. On the side of the displacement, a screw is placed with a small plate attached with a nut so the plate acts a washer. C,D. The clamp is then attached to the head of the screw and is used to pull the hemipelvis forward to reduce the symphysis. A gliding hole must be used so the clamp pulls through the plate and does not rely on the pullout strength of a single screw. (Adapted from Matta JM, Tornetta P. Internal fixation of pelvic fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;329:129–140.)

PLATE PLACEMENT

■Before fixation placement, the reduction should be confirmed on the AP, inlet, and outlet views with the Carm.

■With the symphysis reduced, a six-hole, curved 3.5 reconstruction plate or precontoured plate is placed across the symphysis.

■A Kirschner wire can be placed into the fibrocartilaginous disc space to aid in centering the plate.

■Before the plate is placed, it is contoured to fit the curve of the superior surface of the symphysis and rami. The ends are contoured if a six-hole plate is used to allow for anatomic contact to the ramus (TECH FIG 5A). Alternatively, precontoured plates can be used.

■ In a six-hole plate, the two medial screws on each side go into the symphyseal body and the most lateral screw goes into the rami.

■Careful planning of screw placement must be considered if the Jungabluth clamp is used so that the screws are placed into the plate without loosing the reduction.

■The first screws placed are adjacent to the symphysis on either side (TECH FIG 5B).

■ The drill hole should be placed eccentrically, laterally in the hole to generate compression. The drill should be oriented parallel to the posterior aspect of the symphyseal body.

■ The proper angle can be determined by using a finger to feel the inner surface of the pubic body, using it as a guide for the drill (TECH FIG 5C).

■These initial screws should be angled slightly anteriorly and laterally in the pubic body so that they stay in bone and achieve the best bite.

■ These screws can be placed to go down to the ischium if necessary. Anterior 2 1 Posterior A B C D E TECH

FIG 5 • A. Example of how the plate needs to be contoured to accommodate the pubic tubercle on either side of the symphysis. The concavity of the plate also has to be contoured, and this can vary between genders (see Fig 2). B. Clinical photograph of plate after all screws are placed. Numbering indicates the order of screw placement, with the screws closest to the symphysis being placed first. After screws 1 and 2 are placed, any order may follow for the remaining screws. C. Drilling the proper angle is imperative to ensure the screw will stay in bone. To gauge the angle, one may place a finger on the posterior aspect of the pubic body and then drill parallel to that finger to ensure the drill is held at the proper angle. D–F. Postoperative AP, inlet, and outlet view radiographs of a pre-contoured plate and a reduced symphysis.

■The two most medial screws on each side of the symphysis can be placed either parallel to each other or in a crossing pattern within the symphyseal body (TECH FIG 5D–F).

■The lateral screws in the plate are placed last and will be shorter than the other screws, as they will be at the level of the obturator foramen.

■ When drilling for these screws, care should be taken as the obturator vessels are at risk.

DOUBLE PLATING TECHNIQUE

■Tile described placing a second plate anteriorly if there is no posterior fixation to be placed in vertically unstable patterns (TECH FIG 6).13

■This technique can also be used if insufficient purchase is achieved with initial plate placement.

■In placing the anterior plate, care must be taken in placing screws around the screws of the other plate.

■The same sequence of screw placement should be followed, with the medial screws placed first and subsequent screws placed laterally. TECH FIG 6 • Example of double plating described by Tile.

WOUND CLOSURE

■Once the symphysis is reduced and the plate is in place, a Hemovac is placed in the space of Retzius, between the bladder and the symphysis, and is brought through the rectus fascia.

■After drain placement, the wound is pulse lavaged and the rectus fascia is closed with running heavy absorbable sutures. Care should be taken not to include too many muscle fibers to avoid muscle necrosis.

■Interrupted sutures are used at the distal end to provide a side-to-side closure of the avulsed side.

■The skin is then closed with subcutaneous sutures and staples.

PEARLS AND PITFALLS

Setup

■ It is important to make sure that adequate fluoroscopic AP, inlet, and outlet views can be obtained in the operating room before draping.

Reduction

■ Reduction is confirmed under direct vision as well as on inlet and outlet views of the pelvis. The C-clamp can also be used to maintain reduction before plating if conventional clamps cannot hold the reduction.

Reduction aids

■ A second clamp or a ball-spike can be used to assist in reduction if there is difficulty obtaining reduction or holding the symphysis reduced. For instance, in tilt fractures a ball-spike can be used to push against the intact rami while pulling up the pubic body on the fractured side. Again, the C-clamp or an external fixator can be placed to help approximate the pubic bodies to facilitate reduction with a Weber clamp.

Backup

■ If fixation is tenuous or if the patient becomes too sick to continue with plating, an external fixator can always be added. Screw placement

■ C-arm is used to confirm placement of screws and confirm that they are not too prominent Poor fixation with one plate

■ Double plating can be used to improve fixation by creating a 90-90 construct. Two-hole plate

■ A two-hole plate should not be used: it allows for rotational instability and has a high failure rate. 5

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

■Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis is imperative, as 35% to 60% of patients with a pelvic fracture are at risk. Of these, proximal thrombosis can occur 2% to 10% of the time, and they are at higher risk of developing a pulmonary embolism.6

■With such a high risk of deep venous thrombosis, prophylaxis should consist of a combination of mechanical and chemical means. Venodyne boots or serial compression devices are essential.

■Chemical modalities consist of unfractionated heparin, lowmolecular-weight heparin, vitamin K antagonists, and factor Xa indirect inhibitors.

■If patients have a contraindication for chemical prophylaxis secondary to another injury such as a head bleed, an inferior vena cava filter should be considered.

■Our protocol consists of serial compression devices and subcutaneous heparin three times a day preoperatively. Postoperatively patients are started on low-dose Coumadin. Patients remain on Coumadin for at least 6 weeks, depending on their mobility.

■Early mobilization is imperative to prevent comorbid conditions from arising.

■Once stable fixation is in place, patients should be out of bed to a chair within 24 hours of surgery if their overall condition allows.

■The patient’s weight-bearing status is highly dependent on the operative surgeon understanding the overall injury pattern of the pelvis.

■If anterior fixation is used alone, such as for an APC type II injury, patients are made partial weight bearing for about 8 weeks on the operative side.

■If there is more extensive injury to the posterior pelvis and fixation is required, partial weight bearing should be continued for up to 12 weeks.

■Patients should be followed routinely with radiographs. On postoperative day 1, before the patient gets upright, AP, inlet, and outlet radiographs should be obtained to assess the reduction and more importantly to be used for comparison for future follow-up radiographs taken at 6 and 12 weeks. OUTCOMES

■ Stabilizing the anterior pelvis improves outcomes, and anatomic alignment allows for ligamentous healing.

■Kellam1 defined an adequate reduction of anterior symphyseal widening as less than 2 cm and reported that when this was obtained in rotationally unstable fractures, 100% of patients returned to normal function. Patients with posterior pathology had poor outcomes, with only 31% reporting normal function.

■Pohlemann et al7 reported no residual posterior displacement in 95 patients with type B fractures treated with anterior plating. This was associated with an 11% incidence of late pain that occurred after exercise. No patients had pelvic pain at rest.

■Tornetta et al15,16 also reported that APC type II injuries, when treated with anatomic open reduction and internal fixation, have a 96% rate of good to excellent outcomes.

■Pohlemann et al7 also demonstrated type C injuries radiographically had more residual posterior displacement than type B injuries. Only 33% of these type C patients were painfree after combined anterior and posterior fixation.

■In general, functional outcomes correlate with the initial displacement of the injury.

■Associated injuries will also dictate outcome. Patients with associated urologic injuries are at risk for urethral strictures, urinary tract infections, and even late infections.

■There is a greater than 90% chance of a good outcome in patients with near-anatomic fixation of the symphysis in APC type II pelvic fractures, and about 96% will be able to return to work within a year of injury.15 COMPLICATIONS

■Proximal deep vein thrombosis occurs in 25% to 35% of pelvic fractures, so it is imperative to provide proper prophylaxis both mechanically and chemically.6

■Plates and screws can fracture or loosen secondary to fatigue due to the physiologic motion that is maintained between the two pubic bodies. This tends to occur after 8 weeks and generally does not affect healing.

■If it occurs earlier and a loss of reduction occurs, then revision osteosynthesis should be considered.4,5,16

■Loss of reduction can also occur with widening of the symphysis with and without the plate breaking. Although no data exist, the quality of the initial reduction appears to be the best predictor. Therefore, if a perfect reduction cannot be maintained, additional fixation should be added or activity modification should be implemented postoperatively.5,15

■In most series of pelvic fractures reporting on the use of anterior fixation there is a low incidence of anterior wounds developing deep infections.

■Most resolve with irrigation and débridement and go on to union.2,4,5

■Urologic injuries occur in about 15% of pelvic fractures.

Urologic complications include late urethral strictures, incontinence, and erectile dysfunction.

■Early repair of bladder or urethral injuries at the same time of fixation avoids more complex reconstructions, but the rate of late urologic complications is still relatively high.8 REFERENCES 1. Kellam JF. The role of external fixation in pelvic disruptions. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989;241:66–82. 2. Lange R, Hansen S. Pelvic ring disruptions with symphysis pubis diastasis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1985;201:130–137. 3. Lindsey RW, Leggon RE, Wright DG, et al. Separation of the symphysis pubis in association with childbearing: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988;70A:289–292. 4. Matta JM. Indications for anterior fixation of pelvic fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;329:88–96. 5. Matta JM, Tornetta P. Internal fixation of pelvic fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;329:129–140. 6. Montgomery KD, Geertz WH, Potter HG, et al. Thromboembolic complications in patients with pelvic trauma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;329:68–87. 7. Pohlemann T, Bosch U, Gansslen A, et al. The Hannover experience in management of pelvic fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1994; 305:69–80. 8. Routt ML, Simonian PT, Defalco AJ, et al. Internal fixation in pelvic fractures and primary repairs of associated genitourinary disruptions: a team approach. J Trauma 1996;40:784–790. 9. Siegel J, Tornetta P, Templeman D. Single leg stance views for the diagnosis of pelvic instability. Presented at Orthopaedic Trama Association annual meeting, Boston, 2007. 10. Siegel J, Tornetta P, Burke P, et al. CT angiography for pelvic trauma predicts angiographically treatable arterial bleeding. Presented at Orthopaedic Trauma Association annual meeting, Boston, 2007. 486 Part 2 PELVIS AND LOWER EXTREMITY TRAUMA • Section I PELVIS AND HIP 11. Templeman D, Schmidt A, Sems SA. Diastasis of the symphysis pubis: open reduction and internal fixation. In: Wiss DA, ed. Masters Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery: Fractures, ed 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006:639–649. 12. Tile M. Fracture of the Pelvis and Acetabulum. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1984. 13. Tile M. Pelvic ring fractures: should they be fixed? J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;70B:1–12. 14. Tornetta P, Hochwald N, Levine R. Corona mortis: incidence and location. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;329:97–101. 15. Tornetta P, Dickson K, Matta JM. Outcome of rotationally unstable pelvic ring injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;329:147–151. 16. Tornetta P, Templeman D. Expected outcomes after pelvic ring injury. AAOS Instr Course Lect 2005;54:401–407. 17. Wright RD, Glueck DA, Selby JB, et al. Intraoperative use of the pelvic C-clamp as an aid in reduction for posterior sacroiliac fixation. J Orthop Trauma 2006;20:576–579. 18. Whitbeck MG Jr, Zwally HJ II, Burgess AR. Innominosacral dissociation: mechanism of injury as a predictor of resuscitation requirements, morbidity, and mortality. J Orthop Trauma 1997;11:82–88.

FIG 3 • The hemipelvis externally rotates out when the posterior sacroiliac ligaments remain intact, as in an anterior–posterior compression type II injury. The posterior ligaments act as a hinge, and with sacrospinous ligaments torn the involved hemipelvis will rotate down and out, so the pubic body on the injured side will be below the intact pubic body. compress the bladder or uterus, altering the pelvic ring, it should be reduced to the other pubic body, which remains intact.

FIG 3 • The hemipelvis externally rotates out when the posterior sacroiliac ligaments remain intact, as in an anterior–posterior compression type II injury. The posterior ligaments act as a hinge, and with sacrospinous ligaments torn the involved hemipelvis will rotate down and out, so the pubic body on the injured side will be below the intact pubic body. compress the bladder or uterus, altering the pelvic ring, it should be reduced to the other pubic body, which remains intact.