Plate Fixation of Clavicle Fractures

DEFINITION

■ Displaced, comminuted fractures of the clavicle are at risk for nonunion and malunion3–5,7–9 and can be considered for open reduction and internal fixation with a plate and screws.

ANATOMY

■ The clavicle and scapula are tightly linked through the strong coracoclavicular and acromioclavicular ligaments and link the axial skeleton to the upper extremity.

■ Clavicles are present only in brachiating animals and appar- ently serve to help hold the upper limb away from the trunk to enhance more global positioning and use of the limb.

■ The clavicle is named for its S-shaped curvature, with an apex anteromedially and an apex posterolaterally, similar to the musical symbol clavicula. The larger medial curvature widens the space for passage of neurovascular structures from the neck into the upper extremity through the costoclavicular interval.

■ The clavicle is made up of very dense trabecular bone lacking a well-defined medullary canal. In cross section, the clavicle changes gradually between a flat lateral aspect, a tubular mid- portion, and an expanded prismatic medial end.

■ The clavicle is subcutaneous throughout its length and makes a prominent aesthetic contribution to the contour of the neck and upper part of the chest.

■ The supraclavicular nerves run obliquely across the clavicle just superior to the platysma muscle and should be identified and protected during operative exposure to offset the develop- ment of hyperesthesia or dysesthesia over the chest wall.

PATHOGENESIS

■ Clavicle fractures usually result from a direct blow to the point of the shoulder.

■ This is usually a moderate- to high-energy injury in younger adults but can result from a low-energy fall from a standing height in an older individual.

NATURAL HISTORY

■ The overall nonunion rate for diaphyseal clavicle fractures is

4.5%.7

■ The risk of nonunion increases with age, female gender, dis- placement, and comminution.7

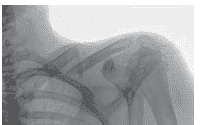

■ The risk of nonunion for completely displaced (no apposition)

and comminuted fractures is between 10% and 20% (FIG 1).9

■ Malunion of the clavicle can result in shoulder girdle defor- mity and weakness.3–5,9

■ Malunion and nonunion of the clavicle can result in brachial plexus compression.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ The mechanism and date of injury should be elicited.

■ A careful neurologic examination should be performed.

■ In contrast to late dysfunction of the brachial plexus after clavicular fracture, a situation in which medial cord struc- tures are typically involved, acute injury to the brachial plexus at the time of clavicular fracture usually takes the form of a traction injury to the upper cervical roots. Such root traction injuries generally occur in the setting of high- energy trauma and have a relatively poor prognosis.

■ “Tenting” of the skin by a fracture fragment is dangerous only in patients who cannot protect their skin (eg, patients who are comatose).

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ An anteroposterior (AP) radiograph can be supplemented by a 20- to 60-degree cephalad-tilted view.

■ The so-called apical oblique view (tilted 45 degrees anterior and 20 degrees cephalad) may facilitate the diagnosis of minimally displaced fractures (eg, birth fractures, fractures in children).

■ The abduction lordotic view taken with the shoulder ab- ducted above 135 degrees and the central ray angled 25 degrees cephalad is useful in evaluating the clavicle after internal fixa- tion. Abduction of the shoulder results in rotation of the clav- icle on its longitudinal axis, which causes the plate to rotate superiorly and thereby expose the shaft of the clavicle and the fracture site under the plate.

■ Computed tomography with 3D reconstructions can help understand 3D deformity.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

■ Lateral or medial clavicle fracture

■ Acromioclavicular or sternoclavicular dislocation

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

■ Closed reduction of clavicular fractures is rarely attempted because the reduction is usually unstable and no reliable means of providing external support is available.

■ A simple sling provides comfort and limits activity during healing. A figure 8 bandage leaves the arm free, but it cannot improve alignment.

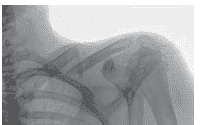

FIG 1 • An AP radiograph shows greater than 100% displace- ment and comminution with a vertical fracture fragment. The clavicle is shortened. (Copyright David Ring, MD.)

■ There is no need to be concerned about shoulder stiffness, and patients should be encouraged keep the arm at the side and limit activity for the first 4 to 6 weeks.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

■ Intramedullary fixation is an option when comminution is limited, but otherwise plate-and-screw fixation is preferred.

■ The plate can be placed on either the superior or the ante- rior1,2 aspect of the clavicle.

Preoperative Planning

■ Planning of the surgery using tracings of radiographs helps limit intraoperative decision making and helps the surgeon anticipate problems and contingencies.

Positioning

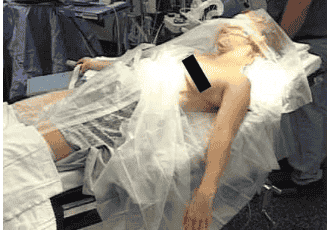

■ The patient is supine with a variable amount of flexion of the trunk according to surgeon preference (FIG 2).

Approach

■ A longitudinal incision is made in line with the clavicle.

FIG 2 • The patient is positioned supine with the head and trunk elevated slightly. (Copyright David Ring, MD.)

SUPERIOR PLATE-AND-SCREW FIXATION

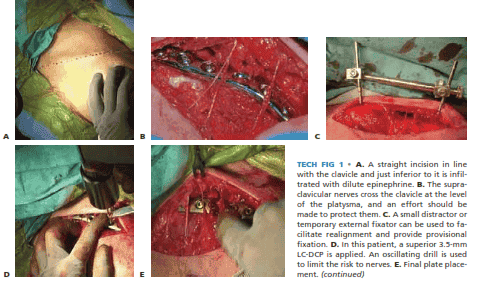

■ An incision is made parallel and just inferior to the long axis of the clavicle (TECH FIG 1A). Infiltration with dilute epinephrine can help limit bleeding.

■ The crossing supraclavicular nerves are identified under loupe magnification and preserved (TECH FIG 1B).

■ Muscle attachments and periosteum are preserved as

much as possible.

■ Realignment and provisional fixation may be facilitated by the use of a small distractor or temporary external fixator (TECH FIG 1C).

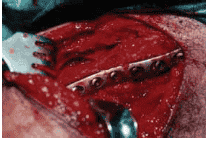

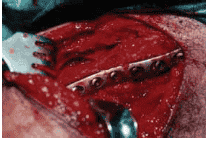

■ A 3.5-mm limited-contact dynamic compression plate (LCDC plate, Synthes) or a precontoured plate is applied to the superior aspect of the clavicle (TECH FIG 1D). A minimum of three screws should be placed in each major fragment. If the fracture pattern is amenable, placement of an interfragmentary screw greatly enhances the sta- bility of the construct.

■ When the vascularity of the fragments has been pre-

served, no bone graft is needed (TECH FIG 1E). When extensive stripping or gaps have occurred in the cortex

TECH FIG 1 • A. A straight incision in line with the clavicle and just inferior to it is infil- trated with dilute epinephrine. B. The supra- clavicular nerves cross the clavicle at the level of the platysma, and an effort should be made to protect them. C. A small distractor or temporary external fixator can be used to fa- cilitate realignment and provide provisional fixation. D. In this patient, a superior 3.5-mm LC-DCP is applied. An oscillating drill is used to limit the risk to nerves. E. Final plate place ment. (continued)

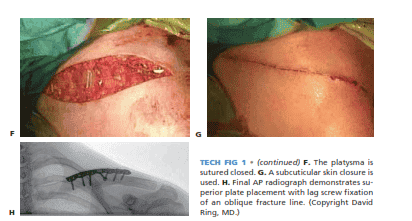

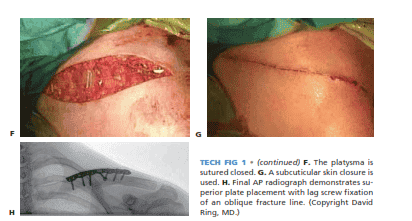

TECH FIG 1 • (continued) F. The platysma is sutured closed. G. A subcuticular skin closure is used. H. Final AP radiograph demonstrates su- perior plate placement with lag screw fixation of an oblique fracture line.

opposite the plate, one might consider adding a small amount of autogenous iliac crest cancellous bone graft.

■ Close the platysma (TECH FIG 1F).

■ If the skin condition is suitable, wound closure is accom- plished in atraumatic fashion with a subcuticular suture (TECH FIG 1G,H).

ANTERIOR PLATE-AND-SCREW FIXATION

■ The technique is identical for an anterior plate place- ment with the exception that the origins of the pec- toralis major and deltoid are partially extraperiosteally elevated off the anterior clavicle (TECH FIG 2).

■ The anterior plate placement may help to decrease hard-

ware prominence, and the drill and screws are directed posterior rather than directly inferior to the clavicle, which may increase the margin of safety.

TECH FIG 2 • An alternative is to place the plate on the anterior surface of the clavicle. This limits plate prominence but requires greater stripping and muscle elevation. (Copyright David Ring, MD.)

PEARLS AND PITFALLS

Supraclavicular nerve neuroma ■ Attempts to identify and protect these nerves are worthwhile.

Brachial plexus stretch injury ■ Realignment should be done gradually and can be facilitated by temporary external fixation.

Pulling fragments out of the wound should be limited.

Loosening of fixation ■ At least three good bicortical screws should be placed on each side of the fracture.

Axial pull-out of locked screws ■ Locking screws may be troublesome when used on the lateral fragment with the plate in a superior position.

Plate prominence ■ Anterior plate placement may diminish plate prominence.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

■ Confident use of the hand at the side is encouraged imme- diately.

■ Shoulder abduction and handling of more than 15 pounds is delayed until early healing is established.

■ Shoulder stiffness is unusual and usually responds quickly to exercises. Shoulder exercises can therefore be delayed until healing is established.

OUTCOMES

■ Plate loosening and nonunion occur in 3% to 5% of cases.6

■ Healing leads to good function.

COMPLICATIONS

■ Infection and wound complications occur but are uncommon.

■ Neurovascular injury is very uncommon and pneumothorax has not been described.

3180 STERNOCLAVICULAR JOINT AND CLAVICLE FRACTURES

REFERENCES

1. Collinge C, Devinney S, Herscovici D, et al. Anterior-inferior plate fixation of middle-third fractures and nonunions of the clavicle. J Orthop Trauma 2006;20:680–686.

2. Kloen P, Sorkin AT, Rubel IF, et al. Anteroinferior plating of midshaft clavicular nonunions. J Orthop Trauma 2002;16:425–430.

3. McKee MD, Pedersen EM, Jones C, et al. Deficits following nonop- erative treatment of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88A:35–40.

4. McKee MD, Wild LM, Schemitsch EH. Midshaft malunions of the clavicle. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85A:790–797.

5. Nowak J, Holgersson M, Larsson S. Can we predict long-term se- quelae after fractures of the clavicle based on initial findings? A

prospective study with nine to ten years of follow-up. J Shoulder

Elbow Surg 2004;13:479–486.

6. Poigenfurst J, Rappold G, Fischer W. Plating of fresh clavicular fractures: results of 122 operations. Injury 1992;23:237–241.

7. Robinson CM, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, et al. Estimating the risk of nonunion following nonoperative treatment of a clavicular fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86A:1359–1365.

8. Robinson CM. Fractures of the clavicle in the adult: epidemiology and classification. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1998;80B:476–484.

9. Zlowodzki M, Zelle BA, Cole PA, et al. Treatment of acute midshaft clavicle fractures: systematic review of 2144 fractures: on behalf of the Evidence-Based Orthopaedic Trauma Working Group. J Orthop Trauma 2005;19:504–507.