Acute Repair and Reconstruction of Sternoclavicular Dislocation

DEFINITION

■ Sternoclavicular dislocation is one of the rarest dislocations, but one most shoulder surgeons will encounter several times during a career (more in a practice with significant exposure to high-energy trauma).

■ The anterior fasciculus arises anteromedially, runs up- ward and laterally, and resists lateral displacement and up- ward rotation of the clavicle.

■ The posterior fasciculus is shorter, arises laterally, runs upward and medially, and resists medial displacement and

■ Sternoclavicular dislocations represented 3% of a series of

excessive downward rotation

(FIGS 1 AND 2).

1603 injuries of the shoulder girdle reported by Cave et al.6

■ The true ratio of anterior to posterior dislocations is un- known, since most reports focus on the rarer posterior type. Estimates range from a ratio of 20 anterior dislocations to each posterior by Nettles and Linscheid,19 in a series of 60 patients (57 anterior and 3 posterior), to a ratio of approximately three to one (135 anterior and 50 posterior) in our series23 of 185 traumatic sternoclavicular injuries.

■ Not all sternoclavicular dislocations require surgery. Avoiding inappropriate patient selection, preventing hard- ware-related complications, and repairing or reconstructing the capsule and the rhomboid ligament if the medial clavicle has been resected require special emphasis.

■ Although this region can be an intimidating one because of the surrounding anatomic structures, a knowledgeable and careful surgeon can treat this joint safely and reliably produce good results.

ANATOMY

■ The epiphysis of the medial clavicle is the last epiphysis of the long bones to appear and the last to close. It does not os- sify until the 18th to 20th year, and it generally fuses with the shaft of the clavicle around age 23 to 25.14,15 For this reason, many sternoclavicular “dislocations” in young adults are in fact physeal fractures.

■ The articular surface of the medial clavicle is much larger than that of the sternum. It is bulbous and concave front to back and convex vertically, creating a saddle-type joint with the curved clavicular notch of the sternum.14,15

■ A small facet on the inferior aspect of the medial clavicle ar- ticulates with the superior aspect of the first rib in 2.5% of subjects.5

■ There is little congruence and the least bony stability of any major joint in the body. Almost all of its integrity comes from the surrounding ligaments.

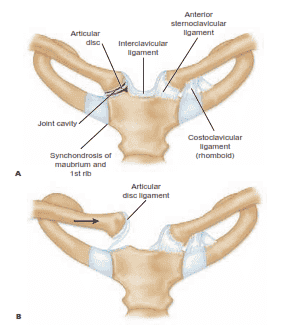

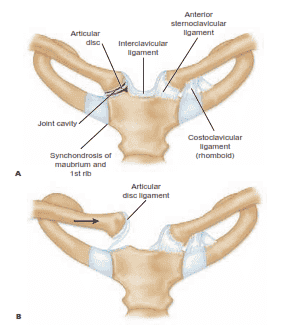

Ligaments

■ The intra-articular disc ligament is dense and fibrous, arises from the synchondral junction of the first rib to the sternum, passes through the sternoclavicular joint, and divides it into two separate spaces14,15 (FIG 1). It attaches on the superior and posterior medial clavicle and acts as a checkrein against medial displacement of the inner clavicle.

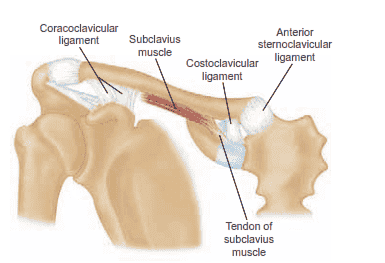

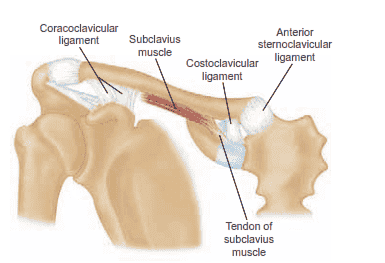

■ The costoclavicular (rhomboid) ligament attaches the upper surface of the medial first rib to the rhomboid fossa on the in- ferior surface of the medial end of the clavicle.14,15 It averages

1.3 cm long, 1.9 cm wide, and 1.3 cm thick.5

■ The interclavicular ligament (see Fig 1) connects the supero-

medial aspects of each clavicle with the capsular ligaments and the upper sternum. Comparable to the wishbone of birds, it helps the capsular ligaments to produce “shoulder poise”; that is, to hold up the lateral aspect of the clavicle.14

■ The capsular ligaments cover the anterosuperior and poste- rior aspects of the joint and represent thickenings of the joint capsule (Figs 1 and 2). The clavicular attachment of the liga- ment is primarily onto the epiphysis of the medial clavicle, with some blending of the fibers into the metaphysis.3,8

■ In sectioning studies, the capsular ligaments are the most important structures in preventing upward displacement of the medial clavicle caused by a downward force on the distal end of the shoulder.1

■ This lateral poise of the shoulder (ie, the force that holds the shoulder up) is attributed to a locking mechanism of the ligaments of the sternoclavicular joint.

■ Other single ligament sectioning studies26 have shown that

the posterior capsule is the most important primary stabilizer to anterior and posterior translation. The anterior capsule is an important restraint to anterior translation. The costoclavic- ular ligament is unimportant if the capsule remains intact,26 although it may be an important secondary restraint if the cap- sular ligaments are torn, much like the coracoclavicular liga- ment laterally.

Applied Surgical Anatomy

■ A “curtain” of muscles—the sternohyoid, sternothyroid, and scaleni—lies posterior to the sternoclavicular joint and the inner third of the clavicle and blocks the view of vital structures—the innominate artery, innominate vein, vagus nerve, phrenic nerve, internal jugular vein, trachea, and esophagus.

■ The anterior jugular vein lies between the clavicle and the curtain of muscles. Variable in size and as large as 1.5 cm in diameter, it has no valves and bleeds like someone has opened a floodgate when nicked.

■ The surgeon who is considering stabilizing the sternoclavic- ular joint by running a pin down from the clavicle into the sternum should not do it and should remember that the arch of the aorta, the superior vena cava, and the right pulmonary artery are also very close at hand.

PATHOGENESIS

■ Most sternoclavicular joint dislocations result from high- energy trauma, usually a motor vehicle accident. They occa- sionally result from contact sports.

we believe that the deformity is less of a problem than the potential complications of operative fixation.

■ When the entire medial clavicle is stripped out of the delto- trapezial fascia, the deformity can be so severe that it may be poorly tolerated, so we consider primary fixation. In those rare cases when a chronic anterior dislocation is sympto- matic, one may perform a capsular reconstruction or a medial clavicle resection and costoclavicular ligament reconstruction.

■ Posterior dislocation

■ In contrast to anterior dislocations, the complications of an unreduced posterior dislocation are numerous: thoracic outlet syndrome, vascular compromise, and erosion of the medial clavicle into any of the vital structures that lie poste- rior to the sternoclavicular joint.

■ Closed reduction for acute posterior sternoclavicular dis- location can usually be obtained, and the reduction is gener- ally stable. Often, general anesthesia is necessary. However, when a posterior dislocation is irreducible or the reduction is unstable, an open reduction should be performed.

■ When chronic posterior dislocation is present, late compli- cations may arise from mediastinal impingement, so we rec- ommend medial clavicle resection and ligament reconstruc- tion.

■ Physeal injuries

■ The typical history for physeal injuries is the same as for other traumatic dislocations. The difference between these injuries and pure dislocations is that most of these injuries will heal with time, without surgical intervention.

■ In very young patients, the remodeling process can elimi-

FIG 1 • A. Normal anatomy around the sternoclavicular joint. The articular disc ligament divides the sternoclavicular joint cavity into two separate spaces and inserts onto the superior and posterior aspects of the medial clavicle. B. The articular disc ligament acts

as a checkrein for medial displacement of the proximal clavicle.

■ A force applied directly to the anteromedial aspect of the clavicle can push the medial clavicle back behind the sternum and into the mediastinum.

■ More commonly, a force is applied indirectly, from the lateral aspect of the shoulder. If the shoulder is compressed and rolled forward, a posterior dislocation results; if the shoulder is com- pressed and rolled backward, an anterior dislocation results.

nate deformity because of the osteogenic potential of an in- tact periosteal tube. Zaslav,31 Rockwood,23 and Hsu et al16 have all reported successful treatment of displaced medial clavicle physeal injury in adolescents and provided radi- ographic evidence of remodeling.

■ Anterior physeal injuries may be reduced, but if reduction cannot be obtained, they can be left alone without problem. Posterior physeal injuries should likewise undergo an at- tempt at reduction. If a posterior dislocation cannot be reduced closed and the patient is having no significant symptoms, the displacement can be observed while remod-

Coracoclavicular

■ As noted above, many injuries of the sternoclavicular joint

in patients under 25 years of age are, in fact, fractures through

ligament

Subclavius muscle

Anterior

sternoclavicular

the medial physis of the clavicle.

NATURAL HISTORY

■ Mild or moderate sprain

■ The mildly sprained sternoclavicular joint is stable but painful.

■ The moderately sprained joint may be slightly subluxated anteriorly or posteriorly, and may often be reduced by drawing the shoulders backward as if reducing and holding a fracture of the clavicle.

■ Anterior dislocation

■ Although most anterior dislocations are unstable after closed reduction, we still recommend an attempt to reduce the dislocation closed.

Costoclavicular

ligament

Tendon of subclavius muscle

ligament

■ Occasionally the clavicle remains reduced, but typically the clavicle remains unstable after closed reduction. We usu- ally accept the deformity, because an anteriorly dislocated sternoclavicular joint typically becomes asymptomatic, and

FIG 2 • Normal anatomy around the sternoclavicular and acromioclavicular joints. The tendon of the subclavius muscle arises in the vicinity of the costoclavicular ligament from the first rib and has a long tendon structure.

FIG 2 • Normal anatomy around the sternoclavicular and acromioclavicular joints. The tendon of the subclavius muscle arises in the vicinity of the costoclavicular ligament from the first rib and has a long tendon structure.

eling occurs. Even in older individuals, a posteriorly dis- placed fracture with moderate displacement and no medi- astinal symptoms may be observed, as it usually becomes asymptomatic with fracture healing.

■ However, as with severely displaced dislocations, one may wish to consider operative repair for severely displaced physeal fractures. Suture repair through the medial shaft and the epiphysis and Balser plate fixation have both been successfully used in this situation.13,27,28

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ A history of high-energy trauma is almost a requirement for the diagnosis. Most cases will be due to a motor vehicle acci- dent, a fall from a significant height, or a sports injury.

■ The absence of such a history suggests either an atrau- matic instability or some other atraumatic condition of the joint.

■ Posterior displacement may be obvious, but anterior fullness can represent either anterior displacement or swelling overly- ing posterior displacement.

■ Careful examination is extremely important. Mediastinal in- juries may occur when a traumatic dislocation is posterior, and the physician should seek evidence of damage to the pul- monary and vascular systems, such as hoarseness, venous con- gestion, and difficulty breathing or swallowing.

■ Evaluation should also include the remainder of the thorax, shoulder girdle, and upper extremity, as well as the contralat- eral sternoclavicular joint.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ Plain radiographs

■ Occasionally, routine anteroposterior chest radiographs suggest displacement compared with the normal side. However, these are difficult to interpret.

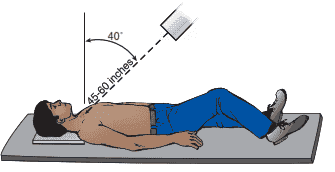

■ Serendipity view: A 45-degree cephalic tilt view is the most useful and reproducible plain radiograph for the sternoclavic- ular joint. The tube is centered directly on the sternum and a nongrid 11 X 14 cassette is placed on the table under the pa- tient’s upper shoulders and neck, so the beam will project the

40˚

medial half of both clavicles onto the film (FIG 3). The tech- nique is the same as a posteroanterior view of the chest.

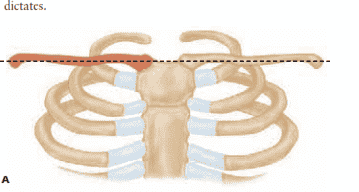

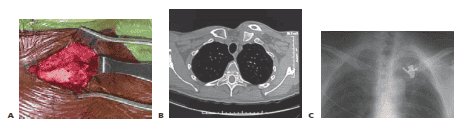

■ An anteriorly dislocated medial clavicle will appear to ride higher compared to the normal side. The reverse is true if the sternoclavicular joint is dislocated posteriorly (FIG 4).

■ In the past, tomograms were useful in distinguishing a stern-

oclavicular dislocation from a fracture of the medial clavicle and defining questionable anterior and posterior injuries of the ster- noclavicular joint. Although they provide more information than plain films, at present they have been replaced with CT scans.

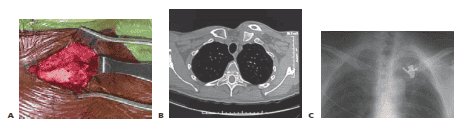

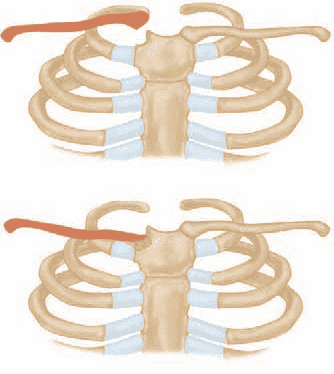

■ Without question, CT scanning is the best technique to study the sternoclavicular joint. It distinguishes dislocations of the joint from fractures of the medial clavicle and clearly de- fines minor subluxations (FIG 5).

■ The patient should lie supine. The scan should include both

sternoclavicular joints and the medial halves of both clavicles so that the injured side can be compared with the normal.

■ If symptoms of mediastinal compression are present or displacement of the medial clavicle is severe, the use of in- travenous contrast will aid in the imaging of the vascular structures in the mediastinum.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

■ Arthritic conditions: sternocostoclavicular hyperostosis, os- teitis condensans, Friedrich disease, Tietze syndrome, and os- teoarthritis

■ Atraumatic (spontaneous) subluxation or dislocation: One or both of the sternoclavicular joints may spontaneously subluxate or dislocate during abduction or flexion during overhead mo- tion. Typically seen in ligamentously lax females in their late teens or early 20s, it is not painful, it is almost always anterior, and it should almost always be managed nonoperatively.22

■ Congenital or developmental or acquired subluxation or dislocation: Birth trauma, congenital defects with loss of bone substance on either side of the joint, or neuromuscular or other developmental disorders can predispose the patient to subluxation or dislocation.

■ Iatrogenic instability may be due to failure to reconstruct the ligaments of the sternoclavicular joint adequately or to an excessive medial clavicle resection. History is significant for a prior procedure on the sternoclavicular joint.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

■ A mild sprain is stable but painful. We treat mild sprains with a sling, cold packs, and resumption of activity as comfort dictates.

X

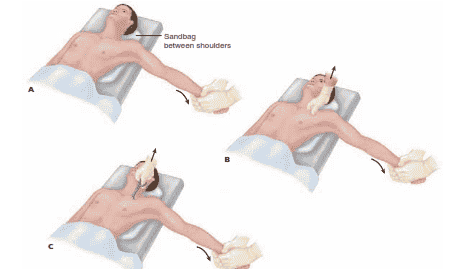

FIG 3 • Serendipity view. Positioning of the patient to take the serendipity view of the sternoclavicular joints. The x-ray tube is tilted 40 degrees from the vertical position and aimed directly at the manubrium. The nongrid cassette should be large enough to receive the projected images of the medial halves of both clavi- cles. In children the tube distance from the patient should be 45 inches; in thicker-chested adults the distance should be 60 inches.

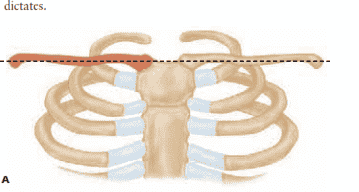

FIG 4 • Interpretation of the cephalic tilt films of the stern- oclavicular joints. A. In a normal person, both clavicles appear on the same imaginary line drawn horizontally across the

film. (continued)

FIG 4 • (continued) B. In a patient with anterior dislocation of the right sternoclavicular joint, the medial half of the right clav- icle is projected above the imaginary line drawn through the level of the normal left clavicle. C. If the patient has a posterior dislocation of the right sternoclavicular joint, the medial half of the right clavicle is displaced below the imaginary line drawn through the normal left clavicle.

FIG 4 • (continued) B. In a patient with anterior dislocation of the right sternoclavicular joint, the medial half of the right clav- icle is projected above the imaginary line drawn through the level of the normal left clavicle. C. If the patient has a posterior dislocation of the right sternoclavicular joint, the medial half of the right clavicle is displaced below the imaginary line drawn through the normal left clavicle.

■ A moderate sprain may be slightly subluxated anteriorly or posteriorly. Moderate sprains may be reduced by drawing the shoulders backward as if reducing a fracture of the clavicle. This is followed by cold packs and immobilization in a padded figure 8 strap for 4 to 6 weeks, then gradual resumption of ac- tivity as comfort dictates.

■ Anterior dislocations may undergo closed reduction with ei- ther local or general anesthesia, narcotics, or muscle relaxants.

■ The patient is supine on the table, with a 3- to 4-inch-thick pad between the shoulders. Direct gentle pressure over the anteriorly displaced clavicle or traction on the outstretched

arm combined with pressure on the medial clavicle will gen- erally reduce the dislocation.

■ Posterior dislocation in a stoic patient may possibly be re- ducible under intravenous narcotics and muscle relaxation. However, general anesthesia is usually required for reduction of a posterior dislocation, because of pain and muscle spasm.

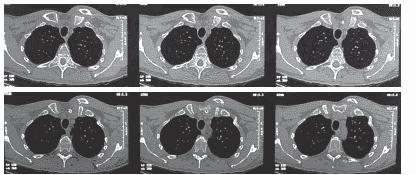

■ Our preferred method is the abduction traction technique.

■ The patient is placed supine, with the dislocated side near the edge of the table. A 3- to 4-inch-thick sandbag is placed between the scapulae (FIG 6). Lateral traction is applied to the abducted arm, which is then gradually brought back into extension. The clavicle usually reduces with an audible snap or pop, and it is almost always sta- ble. Too much extension can bind the anterior surface of the dislocated medial clavicle on the back of the manubrium.

■ Occasionally it is necessary to grasp the medial clavicle with one’s fingers to dislodge it from behind the sternum. If this fails, the skin is prepared, and a sterile towel clip is used to grasp the medial clavicle to apply lateral and an- terior traction (see Fig 6C). If the joint is stable after re- duction, the shoulders should be held back for 4 to 6 weeks with a figure 8 dressing to allow ligament healing.

■ Many investigators have reported that closed reduction usually cannot be accomplished after 48 hours. However, others have reported closed reductions as late as 4 and 5 days after the injury.4

■ Physeal fractures are reduced in the same manner as disloca- tions, with immobilization in a figure 8 strap for 4 weeks to pro- tect stable reductions. Fractures that cannot be reduced and are being managed nonoperatively are treated with a figure 8 strap or a sling for comfort and mobilized as symptoms permit.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

■ A posterior displacement of the medial clavicle that is irre- ducible or redislocates after closed reduction is a well-accepted surgical indication.

■ More controversial is anterior displacement that fails to maintain a stable reduction.

■ Although the traditional treatment for persistent anterior displacement is nonoperative, extreme displacement can re- sult in abundant heterotopic bone formation with accompa- nying pain, limited motion, and extraordinary deformity.

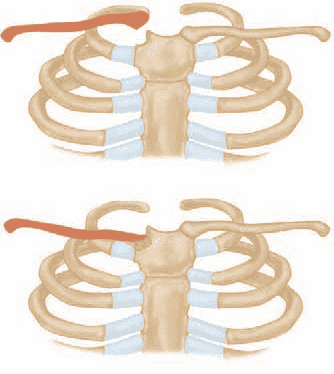

FIG 5 • CT scans of a 6-month-old medial clavicle fracture demonstrate anterior displacement without significant healing.

FIG 5 • CT scans of a 6-month-old medial clavicle fracture demonstrate anterior displacement without significant healing.

FIG 6 • Technique for closed reduction of the sternoclavicular joint. A. The patient is positioned supine with a sandbag placed between the two shoulders. Traction is then applied to the arm against countertraction in an abducted and slightly extended position. In anterior dislocations, direct pressure over the medial end of the clavicle may reduce the joint. B. In posterior dislocations, in addition to the traction it may be necessary to ma- nipulate the medial end of the clavicle with the fingers to dislodge the clavicle from behind the manubrium.

FIG 6 • Technique for closed reduction of the sternoclavicular joint. A. The patient is positioned supine with a sandbag placed between the two shoulders. Traction is then applied to the arm against countertraction in an abducted and slightly extended position. In anterior dislocations, direct pressure over the medial end of the clavicle may reduce the joint. B. In posterior dislocations, in addition to the traction it may be necessary to ma- nipulate the medial end of the clavicle with the fingers to dislodge the clavicle from behind the manubrium.

C. In stubborn posterior dislocations, it may be necessary to prepare the medial end of the clavicle sterilely and

use a towel clip to grasp around the medial clavicle to lift it back into position.

■ We now consider operative treatment when the entire me- dial clavicle is torn out of the deltotrapezial sleeve.

Preoperative Planning

■ Careful review of the history and examination for symptoms of mediastinal compression is crucial.

■ Review of the CT scan for the direction and degree of dis- placement and determination of a very medial fracture versus pure dislocation follows.

■ If history or radiographic evidence of mediastinal compro- mise or potential compromise is present, a cardiothoracic sur- geon should be either present or readily available.

■ Very medial fractures can occasionally be repaired with independent small-fragment lag screws or orthogonal minifragment plates. For pure dislocations, heavy nonab- sorbable suture will sometimes suffice. Suture anchors are useful for augmenting ligament repairs. Allograft tendons may be used if the capsule is irreparable and must be recon- structed.

■ Closed reduction under anesthesia is then attempted and the stability of the joint is evaluated after reduction.

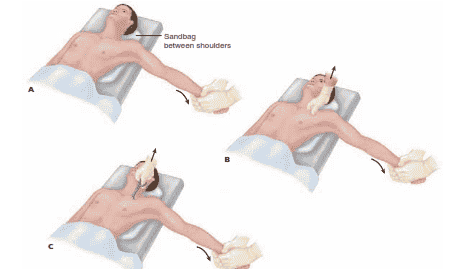

Positioning

■ To begin, the patient is positioned supine on the table, and three or four towels or a sandbag placed between the scapulae.

■ The upper extremity should be draped free so that lateral traction can be applied during the open reduction.

■ A folded sheet may be left in place around the patient’s tho- rax so that it can be used for countertraction.

■ If there is concern regarding the mediastinum, the entire sternum should be draped into the field.

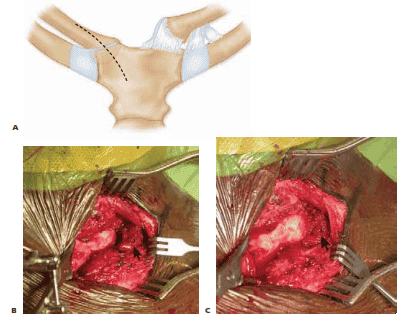

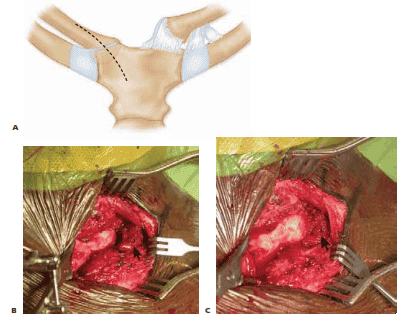

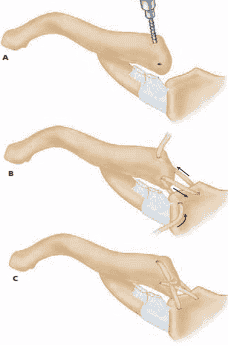

Approach

■ An anterior incision that parallels the superior border of the medial 3 to 4 inches of the clavicle and then extends down- ward over the sternum just medial to the involved sternoclav- icular joint is used (FIG 7A).

■ As an alternative, a necklace-type incision may be created

in Langer’s lines, beginning at the midline and sweeping lat- eral and up along the clavicle.

■ Careful subperiosteal dissection around the medial clavicle and onto the surface of the manubrium allows exposure of the articular surfaces.

■ If the medial clavicle is resting posteriorly, it is safer to identify the shaft more laterally and then trace it back medi- ally along the subperiosteal plane (FIG 7B).

■ Traction and blunt retractors can then be used to lever the

medial clavicle back up into its anatomic location (FIG 7C). These retractors may be used behind the medial clavicle and manubrium to protect the posterior structures.

■ If one has chosen to operate on an anterior medial clavicle because of extreme displacement, it may generally be simply pushed back into place.

FIG 7 • A. Proposed skin incision for open reduction of a posterior dislocation. B. Subperiosteal exposure of the medial clavicle shows a posteriorly displaced medial clavicular shaft (left) resting posterior to the medial clavicular physis (arrow, right). C. The medial shaft of the clavicle has been lifted anteriorly with a clamp and now rests adjacent to the medial physis (arrow, right).

FIG 7 • A. Proposed skin incision for open reduction of a posterior dislocation. B. Subperiosteal exposure of the medial clavicle shows a posteriorly displaced medial clavicular shaft (left) resting posterior to the medial clavicular physis (arrow, right). C. The medial shaft of the clavicle has been lifted anteriorly with a clamp and now rests adjacent to the medial physis (arrow, right).

PRIMARY REPAIR: MEDIAL FRACTURE

■ In children and in young adults, the dislocation of the medial clavicle may occur through the medial physis or as a fracture, leaving a small amount of bone articulating with the manubrium.

■ Because much of the capsule remains intact to this me-

dial fragment, it can serve as an anchor for internal fixa- tion of the medial clavicle shaft. Depending on the amount of bone, the type of fixation will vary.

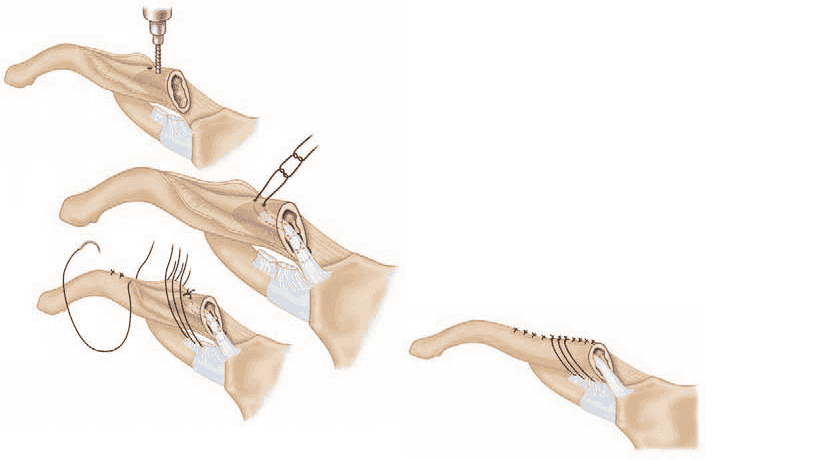

■ The smallest fragments will permit only osseous suture fixation, but the medial clavicle is cancellous bone and heals very quickly (TECH FIG 1A).

■ As the fragment gets larger, independent lag screw fixa-

tion may be possible (TECH FIG 1B,C).

■ For very medial shaft fractures, it may even be possible to use two orthogonal minifragment plates.

TECH FIG 1 • A. Heavy nonabsorbable suture has been placed through drill holes in the medial clavicle and through the physis to secure the fracture shown in Figure 7B,C. B,C. A symptomatic medial clavicle nonunion had a medial fragment large enough to allow fixation with three cortical lag screws.

TECH FIG 1 • A. Heavy nonabsorbable suture has been placed through drill holes in the medial clavicle and through the physis to secure the fracture shown in Figure 7B,C. B,C. A symptomatic medial clavicle nonunion had a medial fragment large enough to allow fixation with three cortical lag screws.

ACUTE REPAIR AND RECONSTRUCTION OF STERNOCLAVICULAR DISLOCATION 3165

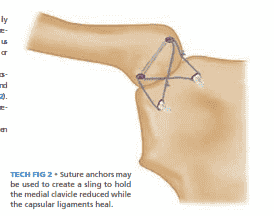

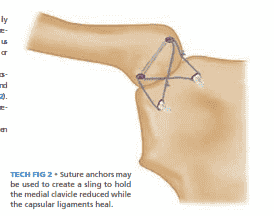

PRIMARY REPAIR: CAPSULAR LIGAMENTS AND SUTURE AUGMENTATION

■ After reduction, the ligaments may be repaired primarily with heavy nonabsorbable suture. This usually allows re- pair of the anterior and superior capsule, but, for obvious reasons, does not allow repair of the important posterior capsule.

■ The reduction is often reinforced with either simple os-

seous sutures through drill holes in the medial clavicle and manubrium27,28 or with suture anchors18 (TECH FIG 2). The costoclavicular ligament may also occasionally be re- paired primarily.

■ This technique has generally been employed in children

but may also be used in adults.

TECH FIG 2 • Suture anchors may be used to create a sling to hold the medial clavicle reduced while the capsular ligaments heal.

TECH FIG 2 • Suture anchors may be used to create a sling to hold the medial clavicle reduced while the capsular ligaments heal.

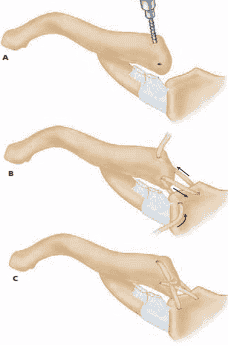

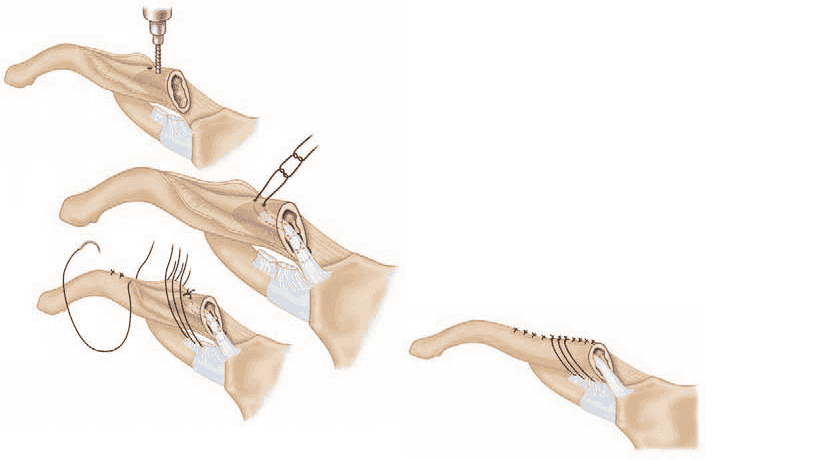

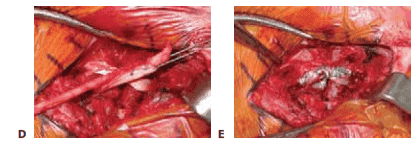

IMMEDIATE RECONSTRUCTION: CAPSULAR LIGAMENTS

■ At times the joint may be reducible but the ligaments are damaged to the point where primary repair is not feasi- ble. In this circumstance, the ligaments may be immedi- ately reconstructed using tendon graft.

■ This may be done by passing a tendon from the front of

the sternum, through the articular surfaces and intra- articular disc, and out the front of the medial clavicle

and tying the tendon to itself anteriorly.20 Autograft or A

allograft tendon may be used.

■ The capsule may also be reconstructed in the manner de- scribed by Spencer and Kuhn25 (TECH FIG 3).

■ Drill holes 4 mm in diameter are created from ante-

rior to posterior through the medial clavicle and the adjacent manubrium.

■ A free semitendinosus tendon graft is woven through

the drill holes so the tendon strands are parallel to each other posterior to the joint and cross each other anterior to it. B

■ The tendon is tied in a square knot and secured with

no. 2 Ethibond suture.

■ This technique has the advantage of reconstructing both the anterior and the posterior ligament in a very strong and secure manner.

C

TECH FIG 3 • A. Semitendinosus may be used to reconstruct the capsular ligaments. B,C. The allograft tendon is pulled through the medial clavicle (left) and manubrium (right) and tied. (continued)

TECH FIG 3 • A. Semitendinosus may be used to reconstruct the capsular ligaments. B,C. The allograft tendon is pulled through the medial clavicle (left) and manubrium (right) and tied. (continued)

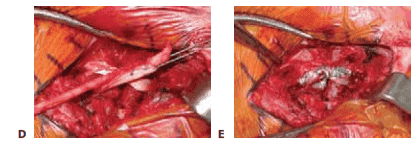

TECH FIG 3 • (continued) D,E. Intraoperative images showing the technique illustrated in B and C. (A–C, After Spencer EE Jr, Kuhn JE. Biomechanical analysis of reconstructions for sternoclavicular joint instability. J Bone Joint

TECH FIG 3 • (continued) D,E. Intraoperative images showing the technique illustrated in B and C. (A–C, After Spencer EE Jr, Kuhn JE. Biomechanical analysis of reconstructions for sternoclavicular joint instability. J Bone Joint

D E Surg Am 2004;86A:98–105.)

MEDIAL CLAVICLE RESECTION AND LIGAMENT RECONSTRUCTION

■ If there is concern about the stability of a reconstruction or repair, if the dislocation is subacute and posterior, or if there is a question of impingement on the mediastinal structures, one may elect to resect the medial clavicle en- tirely. In this situation, it is important to repair or recon- struct the costoclavicular ligament (akin to a modified Weaver-Dunn procedure).

■ The medullary canal can also be used to create an attach-

ment point for an additional medial tether. We prefer to use the patient’s own tissue, such as the sternoclavicular ligament, whenever possible (TECH FIG 4).

■ The medial clavicle is resected and the canal curetted and prepared with drill holes on the superior surface.

■ Grasping suture is woven through the remaining liga-

ment, pulled through the superior drill holes, and tied over bone.

■ Heavy nonabsorbable sutures are then passed through

the remaining costoclavicular ligament and around the clavicle, and the periosteal tube is closed.

■ If adequate local tissue is not present, an allograft such

as Achilles tendon may also be used.2

TECH FIG 4 • The residual capsule may be used to recon- struct a medial clavicular restraint, akin to a medial Weaver-Dunn procedure, as described by Rockwood and Wirth.23

ACUTE REPAIR AND RECONSTRUCTION OF STERNOCLAVICULAR DISLOCATION 3167

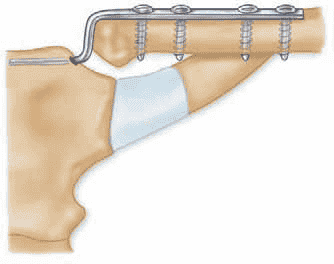

REDUCTION AND BALSER PLATE FIXATION

■ The use of K-wires around the sternoclavicular joint has been routinely condemned, and they should not be used.

■ There are reports, however, of temporary plate fixa-

tion from the medial clavicle to the sternum to main- tain a reduced joint while the soft tissues heal.

■ The Balser plate is a hook plate used in Europe for treat-

ment of acromioclavicular joint separations and distal clavicle fractures. It has been used for sternoclavicular dislocations by placing the hook into the sternum and using screws to fix the plate onto the medial clavicle (TECH FIG 5).

■ Franck et al12 published good results for 10 patients

treated with Balser plates. They thought that the stability of this construct allowed a more rapid reha- bilitation. The implant is quite bulky and removal is generally required.

TECH FIG 5 • Intrasternal Balser (hook) plate insertion.

PEARLS AND PITFALLS

Diagnosis ■ Conventional studies are unreliable. A high index of suspicion, a thorough examination, and a prompt CT scan will ensure correct diagnosis.

Individualize treatment ■ Although anterior dislocations are generally treated nonoperatively, a severely anteriorly

when necessary displaced medial clavicle may be reduced and fixed acutely, with a low risk of complications, in a reliable patient.

■ Posterior dislocations generally mandate surgery because delayed impingement on mediastinal contents may occur. However, there may be situations where displacement is mild and chronic and the risks of surgery may outweigh the benefits.

Prepare for complications ■ Although complications are uncommon, they are spectacular, and not in a good way. The surgeon needs to be ready for both pneumothorax and the unlikely possibility of a vascular injury. A cardiothoracic surgeon should be immediately available.

Use the medial clavicle ■ Even a medial epiphysis or a tiny piece of medial clavicle in its anatomic location provides an excellent anchor for heavy suture or lag screws for primary fracture repair.

Be flexible intraoperatively ■ Preserving the native joint is an admirable goal, but poor ligament and bone quality sometimes precludes primary repair, especially in the subacute dislocation. If the stability of the joint cannot be ensured, medial clavicle resection and costoclavicular reconstruction should be strongly considered.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

■ For sternoclavicular strains and anteriorly dislocated medial clavicles accepted in this position, a sling or figure 8 strap is prescribed and the patient is allowed to mobilize the extremity as function permits.

■ Medial clavicle fractures that are stable after reduction are immobilized in a figure 8 strap for 4 to 6 weeks and then mo- bilized as comfort allows.

■ Acute dislocations that have been reduced and are stable or have been surgically repaired receive a sling or figure 8 strap for 6 weeks to protect the reduction and allow ligament healing.

■ Patients in the figure 8 strap are allowed use of the elbow and hand with the arm at the side for light activities of daily living, but the strap is conscientiously maintained.

■ At 4 to 6 weeks they move to a sling and perform their own mobilization. Because the glenohumeral joint is unaffected, motion usually returns quickly to near full range.

■ When full range of motion has been obtained, gentle pro- gressive strengthening and resumption of normal activities commence.

■ In general, patients treated with joint preservation can re- turn to all activities, including heavy labor, but we have seen traumatic failure of costoclavicular reconstructions and do ask patients who have undergone medial clavicle resection and lig- ament reconstruction to avoid heavy overhead labor for their lifetimes.

OUTCOMES

■ A recent Medline search for “sternoclavicular” and “disloca- tion” yielded 320 citations, most dealing with sternoclavicular instability and its sequelae. Most were case reports, a series of three or four patients, or a discussion of the complications of the injury or its treatment. There are very few large series, which makes discussing outcomes difficult. However, several themes do emerge.

■ The need for proper patient selection becomes evident when one considers that some forms of sternoclavicular instability generally do well when treated without surgery.

■ Sadr and Swann24 and Rockwood and Odor22 have both

documented the good long-term results obtained with nonop- erative treatment of atraumatic sternoclavicular instability.

■ De Jong7 has documented good long-term results in 13

patients with anterior dislocations treated nonoperatively.

■ Several larger series9,11,29 have reported on about a dozen patients treated with open reduction, ligament repair or recon- struction, and fixation with pins or sternoclavicular wiring. Good results were obtained when the medial clavicle was suc- cessfully stabilized.

■ Eskola,10 however, noted a high failure rate if the re-

maining medial clavicle was not successfully stabilized to the first rib.

■ In a separate study, Rockwood et al21 reported on seven

patients who had previously undergone medial clavicle resec- tion without ligament reconstruction. Six of the seven had worse symptoms than before their index procedure.

COMPLICATIONS

■ Complications of injury

■ Anterior dislocation: cosmetic “bump” (which may occa- sionally be pronounced) and late degenerative changes

■ Posterior dislocation: Great vessel injuries, including lacer- ation, compression, and occlusion, pneumothorax, rupture of the esophagus with abscess and osteomyelitis of the clavi- cle, fatal tracheoesophageal fistula, brachial plexus compres- sion, stridor and dysphagia, hoarseness of the voice, onset of snoring, and voice changes from normal to falsetto with movement of the arm have all been reported. These all may occur acutely or in a delayed fashion.

■ Worman and Leagus30 reported that 16 of 60 patients

FIG 2 • Normal anatomy around the sternoclavicular and acromioclavicular joints. The tendon of the subclavius muscle arises in the vicinity of the costoclavicular ligament from the first rib and has a long tendon structure.

FIG 2 • Normal anatomy around the sternoclavicular and acromioclavicular joints. The tendon of the subclavius muscle arises in the vicinity of the costoclavicular ligament from the first rib and has a long tendon structure.

FIG 4 • (continued) B. In a patient with anterior dislocation of the right sternoclavicular joint, the medial half of the right clav- icle is projected above the imaginary line drawn through the level of the normal left clavicle. C. If the patient has a posterior dislocation of the right sternoclavicular joint, the medial half of the right clavicle is displaced below the imaginary line drawn through the normal left clavicle.

FIG 4 • (continued) B. In a patient with anterior dislocation of the right sternoclavicular joint, the medial half of the right clav- icle is projected above the imaginary line drawn through the level of the normal left clavicle. C. If the patient has a posterior dislocation of the right sternoclavicular joint, the medial half of the right clavicle is displaced below the imaginary line drawn through the normal left clavicle. FIG 5 • CT scans of a 6-month-old medial clavicle fracture demonstrate anterior displacement without significant healing.

FIG 5 • CT scans of a 6-month-old medial clavicle fracture demonstrate anterior displacement without significant healing. FIG 6 • Technique for closed reduction of the sternoclavicular joint. A. The patient is positioned supine with a sandbag placed between the two shoulders. Traction is then applied to the arm against countertraction in an abducted and slightly extended position. In anterior dislocations, direct pressure over the medial end of the clavicle may reduce the joint. B. In posterior dislocations, in addition to the traction it may be necessary to ma- nipulate the medial end of the clavicle with the fingers to dislodge the clavicle from behind the manubrium.

FIG 6 • Technique for closed reduction of the sternoclavicular joint. A. The patient is positioned supine with a sandbag placed between the two shoulders. Traction is then applied to the arm against countertraction in an abducted and slightly extended position. In anterior dislocations, direct pressure over the medial end of the clavicle may reduce the joint. B. In posterior dislocations, in addition to the traction it may be necessary to ma- nipulate the medial end of the clavicle with the fingers to dislodge the clavicle from behind the manubrium. FIG 7 • A. Proposed skin incision for open reduction of a posterior dislocation. B. Subperiosteal exposure of the medial clavicle shows a posteriorly displaced medial clavicular shaft (left) resting posterior to the medial clavicular physis (arrow, right). C. The medial shaft of the clavicle has been lifted anteriorly with a clamp and now rests adjacent to the medial physis (arrow, right).

FIG 7 • A. Proposed skin incision for open reduction of a posterior dislocation. B. Subperiosteal exposure of the medial clavicle shows a posteriorly displaced medial clavicular shaft (left) resting posterior to the medial clavicular physis (arrow, right). C. The medial shaft of the clavicle has been lifted anteriorly with a clamp and now rests adjacent to the medial physis (arrow, right). TECH FIG 1 • A. Heavy nonabsorbable suture has been placed through drill holes in the medial clavicle and through the physis to secure the fracture shown in Figure 7B,C. B,C. A symptomatic medial clavicle nonunion had a medial fragment large enough to allow fixation with three cortical lag screws.

TECH FIG 1 • A. Heavy nonabsorbable suture has been placed through drill holes in the medial clavicle and through the physis to secure the fracture shown in Figure 7B,C. B,C. A symptomatic medial clavicle nonunion had a medial fragment large enough to allow fixation with three cortical lag screws. TECH FIG 2 • Suture anchors may be used to create a sling to hold the medial clavicle reduced while the capsular ligaments heal.

TECH FIG 2 • Suture anchors may be used to create a sling to hold the medial clavicle reduced while the capsular ligaments heal. TECH FIG 3 • A. Semitendinosus may be used to reconstruct the capsular ligaments. B,C. The allograft tendon is pulled through the medial clavicle (left) and manubrium (right) and tied. (continued)

TECH FIG 3 • A. Semitendinosus may be used to reconstruct the capsular ligaments. B,C. The allograft tendon is pulled through the medial clavicle (left) and manubrium (right) and tied. (continued) TECH FIG 3 • (continued) D,E. Intraoperative images showing the technique illustrated in B and C. (A–C, After Spencer EE Jr, Kuhn JE. Biomechanical analysis of reconstructions for sternoclavicular joint instability. J Bone Joint

TECH FIG 3 • (continued) D,E. Intraoperative images showing the technique illustrated in B and C. (A–C, After Spencer EE Jr, Kuhn JE. Biomechanical analysis of reconstructions for sternoclavicular joint instability. J Bone Joint