Medial Clavicle Excision and Sternoclavicular Joint Reconstruction

DEFINITION

■ Many pathologic disorders affect the medial clavicle, the most common of which is osteoarthritis.

■ Other conditions include rheumatoid arthritis, seronega- tive spondyloarthropathies, crystal deposition disease, stern- oclavicular hyperostosis, condensing osteitis, and avascular necrosis.6

■ Infection, while rare, must be considered. When suspected, the sternoclavicular joint should be aspirated for culture, Gram stain, and cell counts and then treated with irrigation and débridement.

■ Instability of the sternoclavicular joint is rare but potentially fatal.

■ Traumatic instability is defined by the direction of displace- ment of the clavicular head and is superior, anterior, or poste- rior.

■ Posterior instability has been associated with a variety of potentially fatal comorbidities.

■ Atraumatic instability is usually anterior and is often seen in people with generalized ligamentous laxity.

■ Symptomatic traumatic instability is best treated with closed reduction and possible reconstruction of the joint, not resec- tion of the clavicle head.

ANATOMY

■ The sternoclavicular joint is a saddle-shaped joint that is the most unconstrained joint in the human body.

■ Important ligamentous restraints to motion include the an- terior capsule (restrains anterior and posterior translation), the posterior capsule (restrains posterior translation),10 and the costoclavicular ligament (which is the pivot point for motion in the axial plane).2

■ The interclavicular ligament seems to provide little func- tion (FIG 1).

PATHOGENESIS

■ Osteoarthritis is the most common disorder affecting the medial clavicle that may require surgical excision.

■ Osteoarthritis is most commonly seen in male laborers, in

women in the perimenopausal years, and after radical neck

■ If the force impacts the posterior shoulder, it will push the shoulder girdle anteriorly. The clavicle pivots over the first rib, dislocating the head of the clavicle posteriorly.

■ Direct blows to the sternoclavicular joint can also dislocate the clavicle head posteriorly.

■ Atraumatic instability develops insidiously without a history of trauma.

NATURAL HISTORY

■ Many people have asymptomatic sternoclavicular joint arthritis.

■ Patients with symptoms may find relief with activity modi- fication and time. This is particularly true with the pain and swelling seen in perimenopausal women.

■ Infection may present with a relatively benign clinical pic- ture but will progress and may become serious.

■ It is rare for the sternoclavicular joint to be the primary joint involved in rheumatologic conditions or crystal deposi- tion disease.

Anterior view

Posterior view

dissection. 2 FIG 1 • Anterior and posterior anatomy of sternoclavicular joint. 1, capsule; 2, costoclavicular ligament; 3, interclavicular ligament; 4, sternocleidomastoid tendon.

■ Rheumatologic disorders can affect the sternoclavicular

joint as part of the systemic disease. Involvement of the stern- oclavicular joint is usually late.

■ Other atraumatic conditions are less common and the pathogenesis is largely unknown.

■ Traumatic instability typically develops from a blow to the shoulder girdle.

■ If the force impacts the anterior shoulder, it will push the shoulder girdle posteriorly. The clavicle pivots over the first rib, forcing the head of the clavicle anteriorly.

■ Traumatic instability may result from high-energy injuries (eg, motor vehicle collision) or may be related to contact in athletics.

■ Posterior instability may be life-threatening as the clavicular head may compress vascular structures, the trachea, or the esophagus.

■ Atraumatic instability may have an insidious onset and is often associated with other signs of generalized ligamentous laxity (eg, patellar subluxation, glenohumeral subluxation).

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ Atraumatic disorders

■ Pain at the sternoclavicular joint is localized to the joint and may be referred up the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius.5

■ Infection typically is unilateral and has significant pain and erythema (Table 1).

■ Osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, seronegative spondy- loarthropathies, and sternoclavicular hyperostosis are typi- cally bilateral, with mild pain, and rare erythema.

■ Crystal deposition diseases, condensing osteitis, and

Friedreich’s disease are typically unilateral, and mildly painful.

■ Traumatic disorders

■ With acute traumatic injuries, patients will have signifi-

It very useful to determine whether a dislocation is anterior or posterior.

■ Arteriography should be considered in posterior disloca- tions if vascular injury is suspected.

■ MRI is helpful in atraumatic disorders to evaluate the soft tissues and can delineate marrow abnormalities, joint effu- sions, and disc and cartilage injury.4

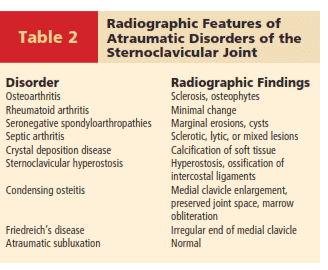

■ Laboratory findings in atraumatic disorders of the stern- oclavicular joint are covered in Table 3.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

■ Atraumatic disorders

■ Osteoarthritis

■ Rheumatoid or other serologic arthritis

■ Seronegative spondyloarthropathies

■ Crystal deposition disease

■ Sternoclavicular hyperostosis

■ Condensing osteitis

■ Avascular necrosis

■ Septic arthritis

■ Instability

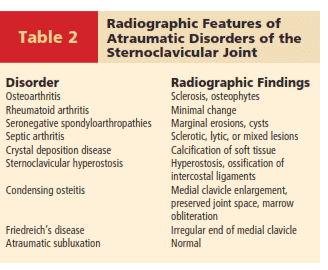

Radiographic Features of

cant pain and will be unwilling to raise the arm. They may describe difficulty with swallowing or breathing in posterior dislocations. Atraumatic Disorders of the

Atraumatic Disorders of the

Sternoclavicular Joint

■ The sternoclavicular joint is often swollen and tender.

■ The affected arm may demonstrate circulatory changes with arm swelling.

■ Physical examination may not be helpful in determining if the instability is anterior or posterior.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ Special radiographic projections include the Rockwood (serendipity), Hobbs, Heinig, and Kattan views but are some- what difficult to interpret (Table 2).4

■ Computed tomography is particularly useful in trauma as it demonstrates displacement of the joint and bony anatomy.4

ANA, antinuclear antibodies; BRFC, birefringement crystals; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, sedimentation rate; RF, rheumatoid factor; WBC, white blood cell count.

■ Traumatic disorders

■ Medial-third clavicle fracture

■ Sternal fracture

■ First rib fracture

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

■ Most atraumatic conditions can be managed nonoperatively.

■ Nonoperative management includes nonsteroidal anti- inflammatories (NSAIDs) and rest. Sometimes topical lido- caine patches can help with pain.

■ Acute dislocations should undergo closed reduction.

■ In posterior dislocations, open reduction and possible recon- struction of the joint is indicated if closed reduction fails.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

■ Surgery is indicated for atraumatic disorders of the stern- oclavicular joint in every case of septic arthritis and when nonoperative management fails for the other conditions listed in the differential diagnosis.

■ When infection is suspected, surgeons should perform inci- sion and drainage quickly to prevent late osteomyelitis.

■ Contraindications for resection of the medial clavicle in- clude atraumatic instability of the joint.

■ Acute dislocations should undergo closed reduction.

■ In posterior dislocations, open reduction and possible recon- struction of the joint is indicated if closed reduction fails.

Preoperative Planning

■ Due to the vital structures that lie behind the sternoclavicu- lar joint, it is important to have a thoracic surgeon available should complications develop.

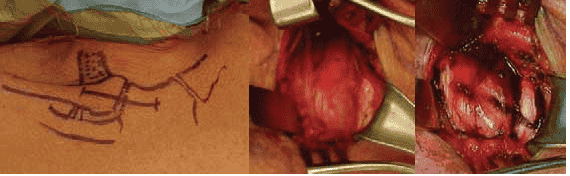

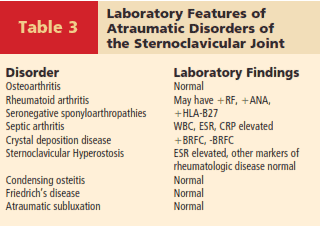

FIG 2 • A. Patient positioning. B. Anatomy is identified and marked.

FIG 2 • A. Patient positioning. B. Anatomy is identified and marked.

Positioning

■ The patient is positioned supine on the operating room table with a small rolled towel behind the middle of the back (FIG 2A).

■ The entire chest is exposed for treatment of complications

should they occur.

■ Important structures, including the clavicle, manubrium, sternocleidomastoid, and costoclavicular ligament, are marked (FIG 2B).

■ The ipsilateral hand is prepared and draped as well if the

surgeon desires to use palmaris as an interposition graft.

■ For reconstructions of the sternoclavicular joint, an ipsilat- eral hamstring may be used; as such, the knee should be pre- pared and draped.

Approach

■ The approach is anterior. Care is taken to protect important structures during dissection, particularly the origin of the ster- nocleidomastoid muscle and the costoclavicular ligament.

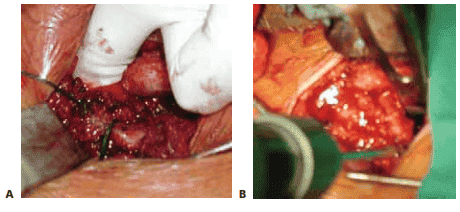

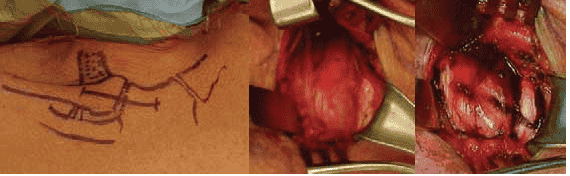

INCISION AND DISSECTION

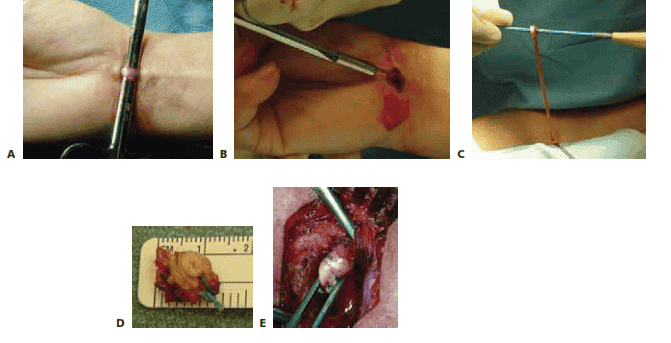

■ The incision is made in the lines of Langer, which follow a necklace pattern over the head of the clavicle and manubrium (TECH FIG 1A).

■ After undermining in the subcutaneous plane, the

platysma is incised in line with the skin incision, exposing

the joint capsule and sternocleidomastoid origin (TECH FIG 1B).

■ The capsule of the joint is marked. Care must be taken to avoid incising the entire sternal head of the sternocleido- mastoid tendon (TECH FIG 1C).

TECH FIG 1 • A. Location of incision. B. Incision of platysma. C. Incision in joint capsule.

TECH FIG 1 • A. Location of incision. B. Incision of platysma. C. Incision in joint capsule.

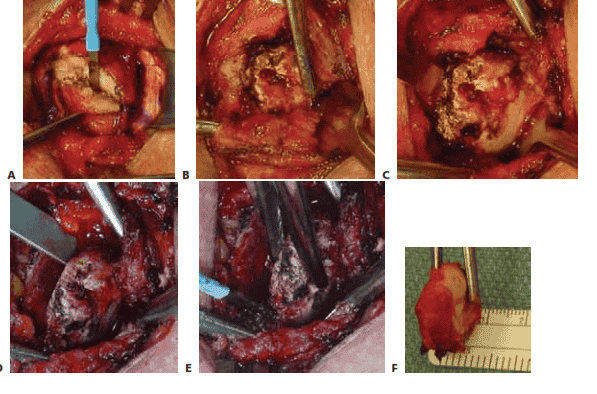

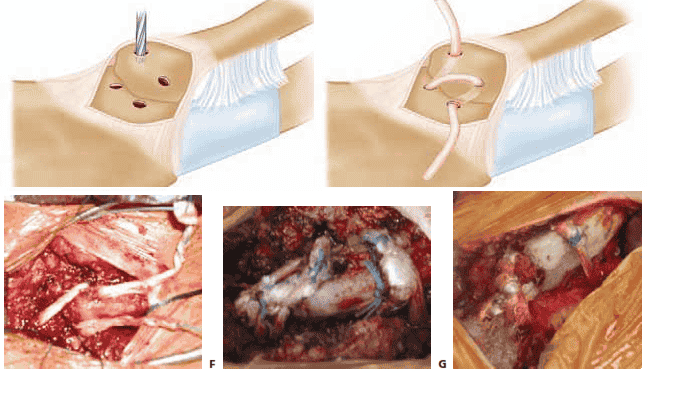

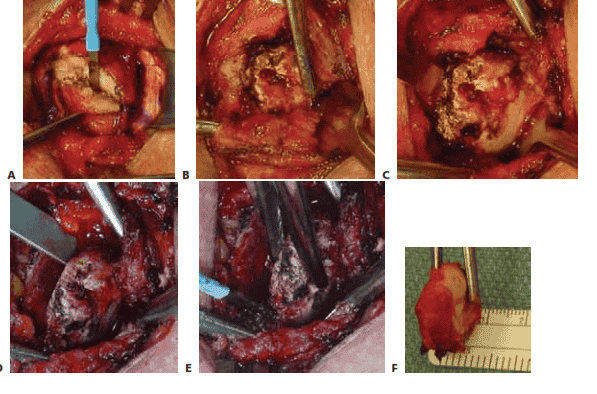

ATRAUMATIC DISORDERS: REMOVING THE BONE

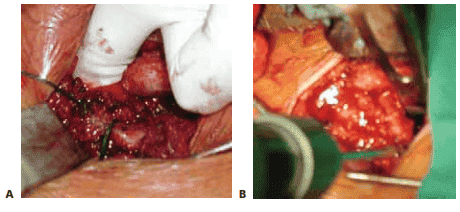

■ Electrocautery can be used to carefully elevate the cap- sule from the clavicular head. It is important to avoid straying too far laterally to avoid detaching the capsule and injuring the costoclavicular ligament (TECH FIG 2A).

■ The intra-articular disc is removed and the capsule is

carefully dissected around the cartilaginous margin of the head of the clavicle (TECH FIG 2B).

■ A self-retaining retractor is placed on the capsule, a

blunt retractor is placed next to the articular surface, and

a small oscillating saw is used to remove between 0.5 and

1.0 cm of the medial clavicle (TECH FIG 2C).

■ An osteotome may be used to lever the medial clavicle head out of the joint (TECH FIG 2D).

■ Electrocautery is used to carefully dissect the posterior cap-

sule from the back of the clavicular head (TECH FIG 2E).

■ The resected head should be between 0.5 and 1.0 cm in size to preserve the costoclavicular ligaments (TECH FIG 2F).3

TECH FIG 2 • A. Elevating the capsule from the clavicle. B. Removing the intra-articular disc. C. Using an oscil- lating saw to remove the medial clavicle. D. Levering the medial clavicle from the joint. E. Removing the poste- rior soft tissue attachments. F. The excised medial clavicle.

TECH FIG 2 • A. Elevating the capsule from the clavicle. B. Removing the intra-articular disc. C. Using an oscil- lating saw to remove the medial clavicle. D. Levering the medial clavicle from the joint. E. Removing the poste- rior soft tissue attachments. F. The excised medial clavicle.

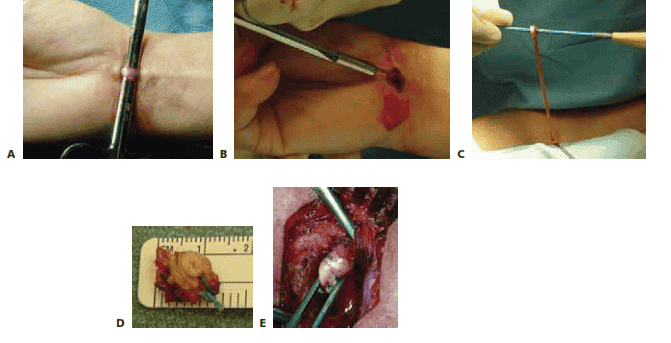

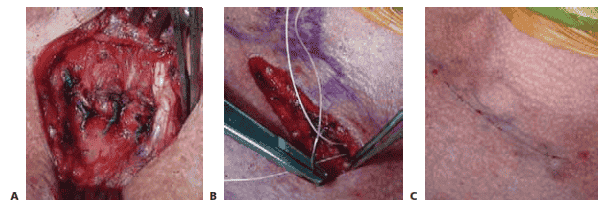

HARVESTING THE TENDON

■ The palmaris tendon is isolated with a small incision in the wrist crease (TECH FIG 3A).

■ After sutures are passed in the end of the palmaris, the

tendon is removed percutaneously with a tendon strip- per (TECH FIG 3B).

■ The harvested tendon is rolled over a small spool and

sutured to itself to create a rolled tendon (TECH FIG 3C,D).

■ When resecting the clavicular head for atraumatic disor- ders, the rolled palmaris tendon is inserted into the de- fect to create a soft tissue interposition between the cut surface of the clavicle and the manubrial joint surface (TECH FIG 3E).

■ Alternatively, the palmaris can be used to augment a re-

construction of an unstable sternoclavicular joint by pass- ing it around the clavicle and first rib (see below).

TECH FIG 3 • A. Palmaris tendon is identified. B. Percutaneous har- vesting of palmaris longus tendon. C. Rolling the palmaris tendon graft. D. The rolled palmaris is sutured to itself. E. Insertion of the

TECH FIG 3 • A. Palmaris tendon is identified. B. Percutaneous har- vesting of palmaris longus tendon. C. Rolling the palmaris tendon graft. D. The rolled palmaris is sutured to itself. E. Insertion of the

D E palmaris as interposition graft.

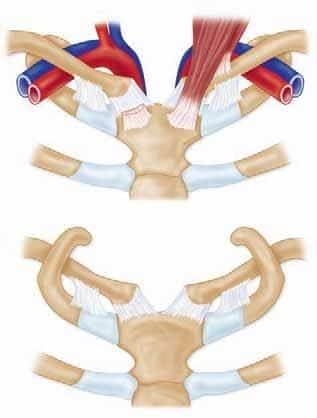

RECONSTRUCTION OF THE STERNOCLAVICULAR JOINT IN INSTABILITY

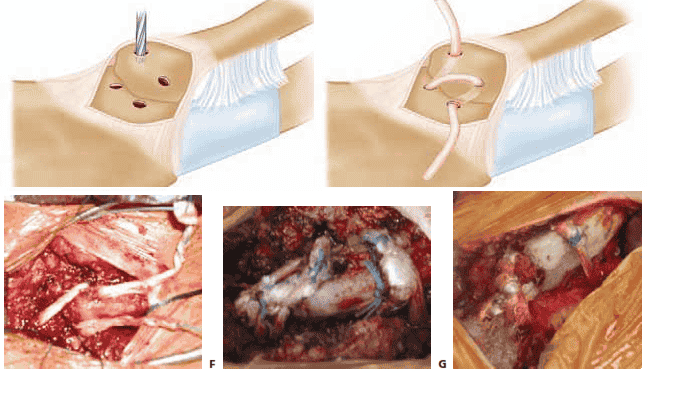

■ A variety of techniques have been described. A figure 8 reconstruction has the best biomechanical properties.11

■ With the assistance of a thoracic surgeon, the plane be-

hind the manubrium is developed by dissecting above the sternal notch (TECH FIG 4A).

■ With a ribbon retractor behind the manubrium, two drill

holes are made in the manubrium and sutures are passed

(TECH FIG 4B).

■ Two drill holes are placed in the medial clavicle from an- terior to posterior (TECH FIG 4C).

■ The semitendinosus autograft is passed in figure 8 fash-

ion and secured to itself (TECH FIG 4D–F).

■ Additionally, the palmaris tendon may be passed around the first rib. This dissection behind the first rib should be performed by the thoracic surgeon to avoid injury to the internal mammary artery (TECH FIG 4G).

TECH FIG 4 • A. Development of the surgical plane behind manubrium. B. Drill holes are in manubrium with protection of mediastinal structures with an

TECH FIG 4 • A. Development of the surgical plane behind manubrium. B. Drill holes are in manubrium with protection of mediastinal structures with an

TECH FIG 4 • (continued) C. Drill holes in clavicle. D–F. Semitendinosus graft is passed in figure 8 fashion. G. Palmaris is passed around clavicle and first rib for augmentation. (C and D, Adapted from Kuhn JE. Sternoclavicular joint reconstruction for an- terior and posterior sternoclavicular joint instability. In Zuckerman J, ed. Advanced Reconstruction of the Shoulder. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2007:255–264.)

TECH FIG 4 • (continued) C. Drill holes in clavicle. D–F. Semitendinosus graft is passed in figure 8 fashion. G. Palmaris is passed around clavicle and first rib for augmentation. (C and D, Adapted from Kuhn JE. Sternoclavicular joint reconstruction for an- terior and posterior sternoclavicular joint instability. In Zuckerman J, ed. Advanced Reconstruction of the Shoulder. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2007:255–264.)

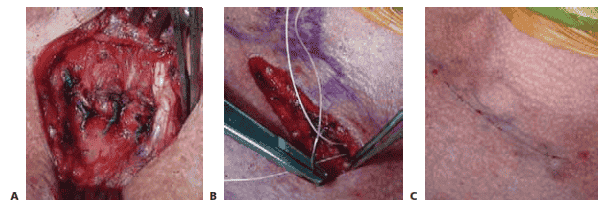

WOUND CLOSURE

■ The capsule is closed with figure 8 interrupted perma- nent number 2 suture, and the sternal head of the stern- ocleidomastoid falls into place (TECH FIG 5A).

■ The wound is closed in layers with 0 Vicryl in the platysma (TECH FIG 5B), 2-0 Vicryl in the subcutaneous layer, and 3-0 Monocryl in the skin (TECH FIG 5C).

TECH FIG 5 • A. Repair of the joint capsule. B. Repair of the platysma. C. Surgical wound is closed.

TECH FIG 5 • A. Repair of the joint capsule. B. Repair of the platysma. C. Surgical wound is closed.

PEARLS AND PITFALLS

Diagnosis ■ CT and MRI imaging will help differentiate arthritis from other less common conditions.

■ The surgeon must always be diligent for infection, which may have a relatively benign appearance.

■ If it is unclear whether the sternoclavicular joint is the source of pain, a diagnostic injection with lidocaine can be helpful.

■ CT is extremely helpful to determine if a dislocation is anterior or posterior.

Removing bone ■ Great care must be taken to avoid perforating the posterior capsule and entering the medi- astinum. It is better to do a partial resection and remove residual bone with a burr.

■ Preserving the clavicular head is important for reconstructions of unstable sternoclavicular joints.

Preserving capsule ■ Maintaining the integrity of the joint capsule is of critical importance. If the capsule is stripped completely off the clavicle, suture anchors in the clavicle can help restore stability.

Costoclavicular ligament ■ If the costoclavicular ligament is sacrificed, the intra-articular disc and disc ligament can be passed into the intramedullary canal.

General surgery ■ It is wise to have a thoracic surgeon available should complications develop in the mediastinum.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

■ Patients are typically admitted overnight for observation.

■ Patients wear a sling with pillow support to support the arm when upright for 6 weeks.

■ Patients are instructed to avoid moving the arm for 6 weeks to allow for capsular healing and preventing instability.

■ After 6 weeks, patients gradually increase range of motion.

■ After 12 weeks, patients can begin strengthening activities.

■ After 16 weeks, patients have unrestricted activity.

OUTCOMES

■ There is little reported on the outcomes after this procedure. All reports are level 4 case series.

■ Rockwood and colleagues9 reported that outcomes were im-

proved if the costoclavicular ligament remained intact (eight of eight excellent with complete satisfaction). If the costoclavicu- lar ligament was disrupted, however, the results were less pre- dictable (three of five excellent).

■ Arcus and associates1 reported on 15 patients with a variety

of pathologies. Sixty percent were graded as good to excellent, and 93% had significant pain relief and would have the pro- cedure again.

■ Pingsmann and colleagues8 found seven of eight women with

sternoclavicular joint arthritis had good to excellent results with medial clavicle excision after 31 months of follow-up.

■ Meis and coworkers7 modified the technique by interpos-

ing the sternal head of the sternocleidomastoid into the de- fect. Ten of 14 patients reported good to excellent outcomes; however, two patients reported incisional pain with head turning, and three patients had cosmesis concerns.

■ A variety of case reports exist for other sternoclavicular joint reconstructions. To date, no reports are in the peer-reviewed literature for the figure 8 reconstruction.

COMPLICATIONS

■ Rockwood and colleagues9 report that patients may have se- vere discomfort if instability persists or develops. Consequently,

it is imperative to preserve the costoclavicular ligament. If the costoclavicular ligament is disrupted, the intra-articular disc and ligament can be transferred into the intramedullary canal of the resected clavicle. In addition, reconstructing the costoclav- icular ligament with a tendon graft around the first rib should be considered.

■ Heterotopic ossification has been reported in about half of the patients but seems to be asymptomatic.1

■ Although not reported to date, complications involving the great vessels, trachea, and other mediastinal contents are pos- sible. A thoracic surgeon should be available for assistance if required.

REFERENCES

1. Acus RW III, Bell RH, Fisher DL. Proximal clavicle excision: an analysis of results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1995;4:182–187.

2. Bearn JG. Direct observations on the function of the capsule of the sternoclavicular joint in clavicular support. J Anat 1967;101:159–170.

3. Bisson LJ, Dauphin N, Marzo JM. A safe zone for resection of the medial end of the clavicle. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003;12:592–594.

4. Ernberg LA, Potter HG. Radiographic evaluation of the acromioclav- icular and sternoclavicular joints. Clin Sports Med 2003;22:255–275.

5. Hassett G, Barnsley L. Pain referral from the sternoclavicular joint: a study in normal volunteers. Rheumatology 2001;40:859–862.

6. Higgenbotham TO, Kuhn JE. Atraumatic disorders of the sternoclav- icular joint. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2005;13:138–145.

7. Meis RC, Love RB, Keene JS, et al. Operative treatment of the painful sternoclavicular joint: a new technique using interpositional arthro- plasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2006;15:60–66.

8. Pingsmann A, Patsalis T, Michiels I. Resection arthroplasty of the sternoclavicular joint for the treatment of primary degenerative ster- noclavicular arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002;84B:513–517.

9. Rockwood CA Jr, Groh GI, Wirth MA, et al. Resection arthroplasty of the sternoclavicular joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997;79A:387–393.

10. Spencer EE, Kuhn JE, Huston LJ, et al. Ligamentous restraints to anterior and posterior translation of the sternoclavicular joint. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002;11:43–47.

11. Spencer EE, Kuhn JE. Biomechanical analysis of reconstructions for sternoclavicular joint instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86A:

98–108.

Atraumatic Disorders of the

Atraumatic Disorders of the

FIG 2 • A. Patient positioning. B. Anatomy is identified and marked.

FIG 2 • A. Patient positioning. B. Anatomy is identified and marked. TECH FIG 1 • A. Location of incision. B. Incision of platysma. C. Incision in joint capsule.

TECH FIG 1 • A. Location of incision. B. Incision of platysma. C. Incision in joint capsule. TECH FIG 2 • A. Elevating the capsule from the clavicle. B. Removing the intra-articular disc. C. Using an oscil- lating saw to remove the medial clavicle. D. Levering the medial clavicle from the joint. E. Removing the poste- rior soft tissue attachments. F. The excised medial clavicle.

TECH FIG 2 • A. Elevating the capsule from the clavicle. B. Removing the intra-articular disc. C. Using an oscil- lating saw to remove the medial clavicle. D. Levering the medial clavicle from the joint. E. Removing the poste- rior soft tissue attachments. F. The excised medial clavicle. TECH FIG 3 • A. Palmaris tendon is identified. B. Percutaneous har- vesting of palmaris longus tendon. C. Rolling the palmaris tendon graft. D. The rolled palmaris is sutured to itself. E. Insertion of the

TECH FIG 3 • A. Palmaris tendon is identified. B. Percutaneous har- vesting of palmaris longus tendon. C. Rolling the palmaris tendon graft. D. The rolled palmaris is sutured to itself. E. Insertion of the TECH FIG 4 • A. Development of the surgical plane behind manubrium. B. Drill holes are in manubrium with protection of mediastinal structures with an

TECH FIG 4 • A. Development of the surgical plane behind manubrium. B. Drill holes are in manubrium with protection of mediastinal structures with an TECH FIG 4 • (continued) C. Drill holes in clavicle. D–F. Semitendinosus graft is passed in figure 8 fashion. G. Palmaris is passed around clavicle and first rib for augmentation. (C and D, Adapted from Kuhn JE. Sternoclavicular joint reconstruction for an- terior and posterior sternoclavicular joint instability. In Zuckerman J, ed. Advanced Reconstruction of the Shoulder. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2007:255–264.)

TECH FIG 4 • (continued) C. Drill holes in clavicle. D–F. Semitendinosus graft is passed in figure 8 fashion. G. Palmaris is passed around clavicle and first rib for augmentation. (C and D, Adapted from Kuhn JE. Sternoclavicular joint reconstruction for an- terior and posterior sternoclavicular joint instability. In Zuckerman J, ed. Advanced Reconstruction of the Shoulder. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2007:255–264.) TECH FIG 5 • A. Repair of the joint capsule. B. Repair of the platysma. C. Surgical wound is closed.

TECH FIG 5 • A. Repair of the joint capsule. B. Repair of the platysma. C. Surgical wound is closed.