Operative Treatment of Radius and Ulna Diaphyseal Nonunions

DEFINITION

■ A diaphyseal forearm fracture is generally considered to be a nonunion if healing has not taken place within 6 months.

■ Nonunions are generally classified as hypertrophic or atrophic, an important distinction in treatment selection.

■ Hypertrophic nonunions have abundant callus and a rich blood supply and result from inadequate stability of fracture fixation. This type of nonunion is rare in the forearm and constitutes less than 10% of nonunion cases.9

■ Atrophic nonunions are characterized by poor blood supply and little or no callus formation.

■ Nonunion of the forearm diaphysis is rare because of the success of current techniques of plate and screw fixation. Nonunion rates of only 2% in the radius and 4% in the ulna are reported.2

ANATOMY

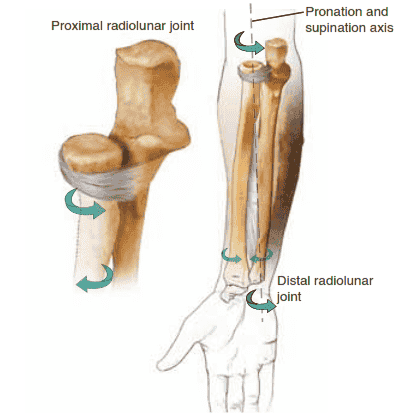

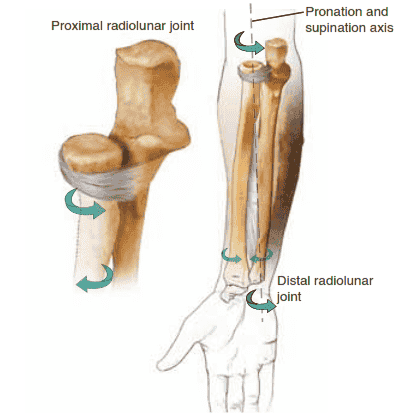

■ The forearm consists of the radius and ulna, joined at either end by the proximal and distal radioulnar joints (PRUJ and DRUJ, respectively) (FIG 1).

■ The ulna is straight, while the radius has both an apex ra-

■ Both the curvature of the radius and the integrity of the interosseous space and interosseous membrane (IOM) must be maintained for the forearm “joint” to function optimally.

■ The diaphyseal portions of the radius and ulna are surrounded by complex anatomy, including neural and vascular structures, that must be considered during any surgical approach. Both radius and ulna are covered by muscle proximally, while the ulna emerges distally to be subcutaneous.

PATHOGENESIS

■ Nonunions of the diaphysis of the forearm are rare and result most commonly from incorrect or inadequate treatment.

■ Inadequate fixation, generally less than six cortices of screw fixation proximal and distal to the fracture, will increase the rate of nonunion.

■ Lack of attention to critical surgical principles such as creating compression across the fracture site (either with the use of an interfragmentary screw or a compression plate) also leads to nonunion.

■ Nonoperative treatment results in markedly increased rates

dial and apex dorsal curvature.

of nonunion and other complications.

With the exception of

■ It can help to think of the forearm as a joint rather than a pair of long bones.

■ Pronation and supination are achieved by rotation of the curved radius about the straight ulna.

Pronation and

isolated, minimally displaced ulnar shaft fractures, all adult

diaphyseal forearm fractures require operative management.

■ Comminution increases the risk of nonunion, with 12% of comminuted, diaphyseal fractures going on to develop nonunion after treatment with dynamic compression plates.11

■ Fracture characteristics that increase the risk of nonunion include extensive devascularization and periosteal stripping,

bone loss, and infection.

■ Open, comminuted fractures with bone loss have the highest rate of nonunion.7

■ Patient comorbidities known to increase rates of nonunion include diabetes mellitus, steroid use, malnutrition, and renal dysfunction.

NATURAL HISTORY

■ Once a nonunion of the forearm is established, it will not go on to heal spontaneously.

■ If significant shortening of either the radius or ulna occurs, the intricate anatomy of the entire forearm “joint” can be disrupted. Malalignment of the DRUJ secondary to such shortening can cause pain and lead to loss of motion at the wrist.

■ Loss of motion secondary to pain, particularly pronation and supination, can lead to shortening and fibrosis of the IOM. This can lead to permanent loss of rotational motion in the forearm.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ Patients with nonunion of the diaphysis of the radius or ulna

FIG 1 • The two bones of the forearm form a functional unit, with the axis of rotation extending from the radiocapitellar joint to the distal radioulnar joint.

most commonly present with pain.

■ This pain frequently worsens with attempts to use the extremity for lifting or pushing, but may also occur at rest.

■ Resisted rotational movements are frequently painful, such as turning a key in a lock.

■ It is important to explore whether infection could be the cause of the nonunion. Important history includes whether or not the original fracture was open, whether postoperative complications or drainage developed, and whether the patient has received antibiotics.

■ During the physical examination, the examiner should do the following:

■ Palpate the nonunion site for pain.

■ Grasp the bone on either side of the nonunion and attempt to flex and extend the nonunion to assess fracture stability and healing. Palpable motion and increased pain indicate lack of union.

■ Loss of flexion–extension in the elbow may result from pain. Loss of pronation and supination indicates deranged forearm anatomy or pain.

■ Loss of flexion or extension at the wrist may indicate pain or scarring of muscle and tendons or IOM around the nonunion. Loss of radioulnar deviation may indicate DRUJ abnormality secondary to shortening at the nonunion site.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

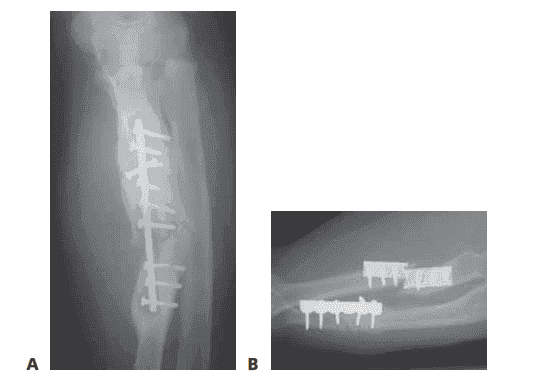

■ Plain radiographs are essential for diagnosis. This should include AP and lateral views of the forearm, elbow, and wrist.

■ Comparative views of the contralateral forearm, elbow, and wrist are also essential for preoperative planning.

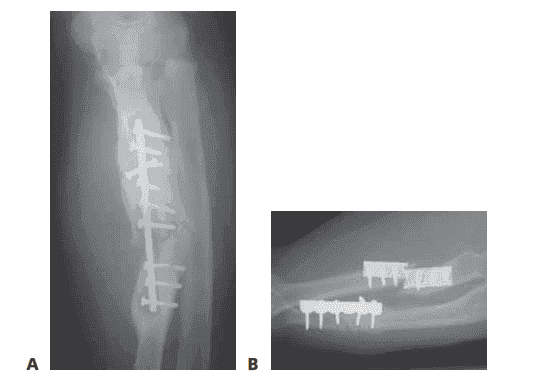

■ Plain radiographs will allow the surgeon to determine if the nonunion is hypertrophic (FIG 2A) or atrophic (FIG 2B).

■ CT is helpful in identifying synostosis, assessing rotational

deformity, and evaluating the size of the gap between bone ends at the nonunion site. CT also allows assessment of the DRUJ and PRUJ.

■ The metal suppression CT technique minimizes the bright scatter created by retained hardware.

FIG 2 • A. Radiograph showing an infected, hypertrophic nonunion. The abundant callus formation indicates a biologically active nonunion. B. Radiograph showing an atrophic nonunion. There is complete absence of callus at the fracture site. The problem in an atrophic nonunion is lack of biologic activity. (Courtesy of Thomas R. Hunt III, MD.)

■ MRI is rarely used but can allow further evaluation of the IOM.

■ A technetium-99m bone scan followed by an indium-

111–labeled leukocyte scan may be indicated when suspicion of an infected nonunion exists.

■ False-positive and false-negative results occur.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

■ Malunion

■ Infection

■ IOM injury

■ Painful hardware

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

■ The goal of treatment is to alleviate pain and restore function to the forearm. This can rarely be accomplished without surgical intervention.

■ In rare circumstances (if the patient is a high risk for surgery due to comorbidities, for example), an external bone stimulator can be used.

■ A minority of patients develop a stable, fibrous nonunion that is painless and allows good function. Nonoperative management can be considered in such patients.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

■ In all nonunions of the forearm, the first considerations are the patient’s level of pain and function.

■ The surgeon should not elect to operate based on radiographic findings alone.

■ All patients with nonunions should undergo a workup to determine if the cause of the nonunion is infection, particularly after open fractures.

■ The workup should include careful history of open fracture, drainage, or postoperative complications after initial surgery.

■ Blood should be obtained for a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein.

■ Nuclear medicine imaging should be performed if the suspicion of infection is high.

Preoperative Planning

■ All imaging studies should be reviewed and pathoanatomy recognized.

■ Plain radiographs should be reviewed for presence or absence of callus in order to categorize the nonunion as hypertrophic or atrophic.

■ If a nonunion of the forearm is hypertrophic (which is rare), it may be treated by simple revision of hardware, creating compression across the fracture site with either a compression screw or a compression plate. This is the same technique that should be used for initial management of radius or ulna fractures (see Chap. HA-4).

■ If any possibility of infection at the nonunion site exists, plans must be made to search for infection when the nonunion site is opened, and to have an alternative treatment plan if infection is encountered.

■ Preoperative antibiotics may be held until cultures are obtained from the nonunion site (ensure the tourniquet is not inflated if antibiotics are administered later in the case).

■ Intraoperative culture swabs and tissue for aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal cultures should be obtained from sites within the nonunion.

■ Patients should be made aware that if severe infection is encountered, the planned procedure may need to be altered. For example, if frank purulence is encountered, the nonunion repair may be abandoned in favor of débridement and irrigation with possible antibiotic bead placement and even external fixation if stability is compromised.

■ Template the radiographs to ensure selection of proper plate size and length.

■ DCP, LCDCP, and combination locking plates are all appropriate.

■ A minimum of six cortices of screw purchase proximal and distal to the nonunion is critical. This may require plates longer than those available in a standard plating set.

■ In osteoporotic bone, the use of locking plates should be considered.

■ If bone graft will be required, the type of graft should be determined preoperatively. While autograft is still considered the gold standard, a vast array of bone graft substitutes are now available. The surgeon’s preference and familiarity with various bone graft substitutes may guide this choice. It is important to determine if a structural graft will be required, as this may necessitate the use of autograft.

■ Patients should be counseled regarding the possible need for (and risks associated with) various types of autograft, including the possible need for a tricortical iliac crest or fibula graft if significant bone loss is encountered.

■ A vascularized fibula graft may be used to fill large defects, especially those associated with infection.1,4,6,12

■ A complete examination of range of motion of the elbow and wrist, including pronation and supination, should be performed under anesthesia.

Positioning

■ The patient should be positioned supine with the operative arm extended on a radiolucent arm table.

■ A nonsterile or sterile tourniquet may be applied, but full access to the elbow is necessary.

■ Because restoration of the radial bow is a critical component in restoring forearm motion, intraoperative radiographs showing the entire radius are essential. For this reason, use of the mini C-arm should be avoided in favor of regular fluoroscopy, with its much larger field of view.

■ The selected site for harvest of autograft should also be prepared and draped.

Approach

■ The approach to either the radius or ulna should generally be through the original surgical incisions.

■ Approach to the radius is most commonly volar through the standard Henry approach. Proximal nonunions of the radius may be more easily accessed via a dorsal Thompson approach, particularly in muscular individuals.

■ Care should be taken to identify and protect the posterior interosseous nerve during this approach.

■ The ulna is accessed along the subcutaneous border in the interval between the flexor carpi ulnaris and the extensor carpi ulnaris.

■ Care should be taken to identify and protect the dorsal cutaneous branch of the ulnar nerve distally.

■ In all cases, preservation of blood supply is key to healing of a nonunion. Therefore, periosteal stripping should be kept to a minimum and the use of cautery should be restricted to vessel coagulation.

PLATE FIXATION FOR TREATMENT OF FOREARM NONUNIONS

Preparation of the Nonunion

■ Determine the correct length of the radius or ulna by measuring the corresponding contralateral bone.

■ Expose the nonunion site and search for evidence of

infection. If found, send specimens for Gram stain and culture and abort the planned procedure. Perform a two-stage reconstruction.

■ Thoroughly débride all necrotic and infected bone

and soft tissue. Remove all hardware.

■ Place antibiotic-loaded PMMA beads in the gap.

■ Begin a multiweek course of antibiotics before proceeding with definitive nonunion repair.

■ If infection is considered unlikely, after removal of all

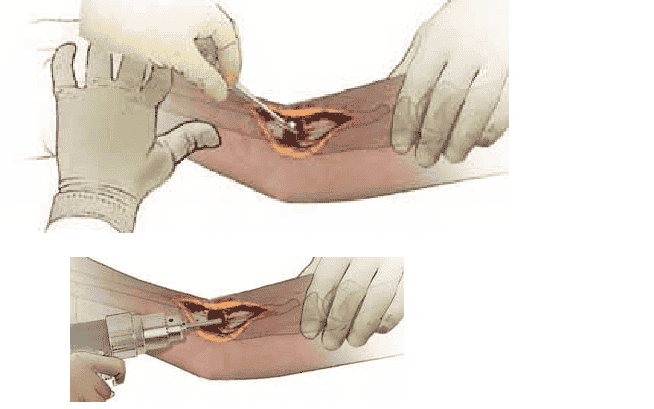

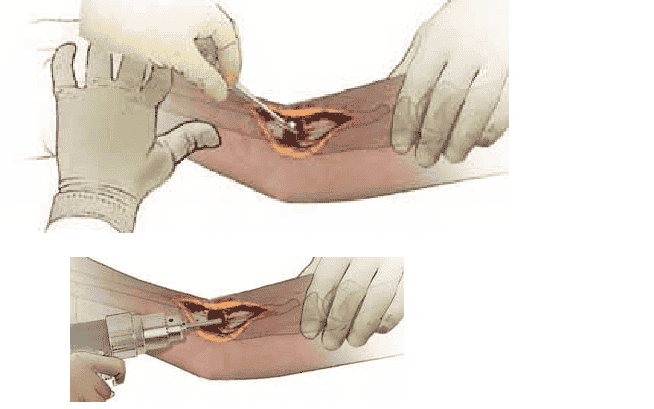

hardware, thoroughly débride the nonunion site of all necrotic and inflammatory tissue, synovial membranes, and sclerotic or avascular bone (TECH FIG 1A).

■ Tools such as curved curettes, small rongeurs, and a

small high-speed burr (with copious irrigation to prevent thermal injury to the bone) are helpful.

■ Flatten the bone ends to allow for excellent frag-

ment-to-fragment contact with compression.

■ Open the sclerotic bone ends using sequentially larger diameter drills.

■ Pass these drills proximally and distally as far as possi-

ble to open the medullary canals (TECH FIG 1B).

■ Restrict elevation of muscle and periosteum to only what is needed to thoroughly débride the nonunion and to realign the bone.

■ Realign the bone and restore length by manipulating

fragments with bone-holding forceps.

■ Use of a small skeletal distractor, small external fixator, or lamina spreader aids in restoration of length.10

■ Measure the length of the residual bone defect directly

and, taking into consideration the preoperative plan, determine the appropriate bone graft to use.

Compression Plating Without

Bone Graft

■ In rare cases with minimal or no bone loss at the nonunion site, the bone may be plated in situ without causing shortening. Because the bone remains at normal

TECH FIG 1 • A. Complete débridement of the nonunion site is the essential first step. Any fibrous or necrotic material must be removed and the bone ends delivered. B. Medullary canals are opened using in creasing-diameter drill bits to allow vascular ingrowth.

length, the relationship of the radius and ulna at both the DRUJ and the PRUJ is not disrupted and rotation will be preserved.

■ This technique may also be used if there is nonunion

of both the radius and the ulna. Both bones may then be shortened a symmetrical distance.

■ After bone preparation as detailed above, anatomically

align the bone ends and precisely apply a compression plate using the same technique employed for acute forearm fractures.

■ Ensure that compression of the bone ends is achieved.

■ If a small bone gap exists after compression, the other forearm bone may then be shortened to restore the length relationship.

■ Because this approach involves surgery on a normal

bone, this strategy should be used with caution.

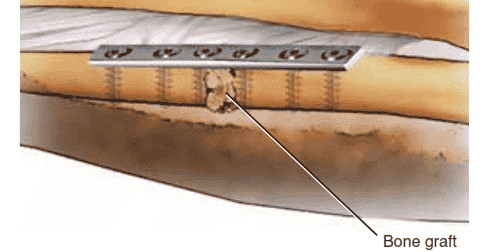

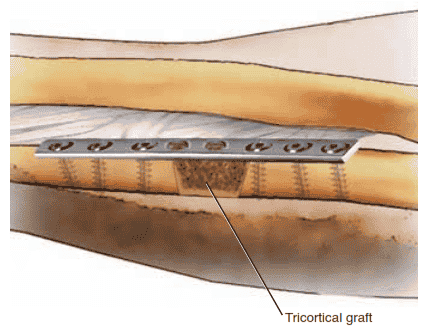

Cancellous Bone Grafting

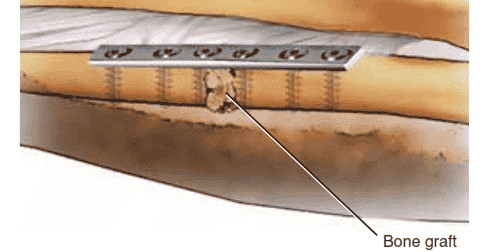

■ Cancellous bone grafting is generally used for small defects up to 3 cm that can be effectively stabilized with a plate.

■ Gaps of up to 6 cm have been successfully treated

using cancellous bone for grafting.9

■ Firmly pack the cancellous autograft into the residual nonunion defect after the plate is applied.

■ Ensure the graft does not escape from the nonunion site

and come to lie on the IOM (TECH FIG 2).

Structural Corticocancellous

Autograft Bone Grafting

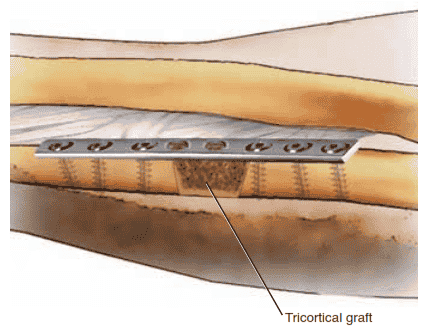

■ Structural autograft harvested from the anterior or posterior iliac crest is used for larger defects.

■ Expose the superior crest and define the inner and outer

tables.

■ Utilize a water-cooled sagittal saw and osteotomes to harvest a tricortical block of bone from the iliac crest. Additionally, harvest cancellous bone to fill defects that may present.

■ The graft should be slightly larger than that required based on preoperative planning.

■ Precisely contour the graft to fit snugly into the defect.

Square the ends of the graft to match the ends of the bone fragments.5

■ Alternatively, cut both the bone ends of the radius or

ulna and of the bone block chamfered, or on the bias, to increase the area of bony contact.3 This also allows the graft to be wedged securely in place.

■ Insert the graft before plate fixation and fill any residual

gaps with cancellous bone after plate application.

Bone graft

TECH FIG 2 • The nonunion gap is distracted if necessary to recreate the normal anatomic bone length. A 3.5-mm plate with a minimum of three screws proximal and distal should be used. Cancellous bone graft is inserted and packed in the nonunion gap.

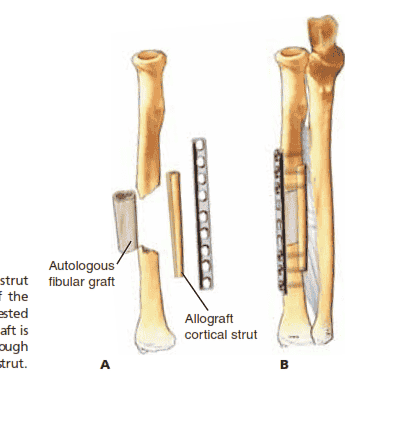

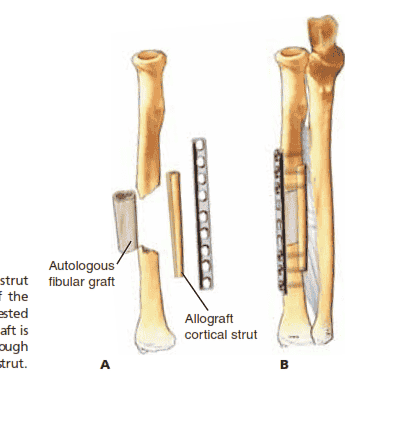

Nonvascularized Structural Fibula Autograft With Cortical Allograft Bone Grafting

■ An appropriate-length segmental graft is harvested from the fibula and placed into the defect.

■ The fibula is approached laterally, via the intramuscular

plane between the peroneal muscles and the soleus.

■ A cuff of muscle 2 to 3 mm in thickness should be left to protect the periosteum.

■ The IOM is incised longitudinally, taking care to avoid

the posterior neurovascular bundle.

■ The fibula is osteotomized proximally and distally to create an appropriate-length graft.

■ Complications of fibular harvest are rare but include

transient motor weakness, peroneal nerve palsy, and flexor hallucis longus (FHL) contracture.

■ A minimum of 6 cm of the distal fibula must be

retained to avoid adversely affecting the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis and ankle joint function.

■ Insert the fibula graft into the defect and then apply the

plate as described below, first placing the two screws just proximal and just distal to the nonunion to gain initial compression.

■ Select a cortical allograft several centimeters longer than

the defect.

■ Tibial allograft is recommended due to its suitable thickness and mechanical characteristics, which provide excellent screw purchase.8

■ Place the cortical allograft along the outer cortex of the

bone, opposite the plate, spanning beyond the length of the fibula allograft.

■ Insert the remainder of the screws so that they pass

through the plate and then the patient’s bone and finally into the cortical allograft on the opposite side (TECH FIG 3).

T

COMPRESSION PLATE FIXATION

■ Select a 3.5-mm (small fragment) compression plate of adequate length to ensure a minimum of three or four screws (six to eight cortices) on either side of the nonunion.

■ Always err on the side of a longer plate.

■ Thinner locking plates may be considered when structural fibular autografts are combined with cortical allograft struts.

■ Fix the plate to the bone in compression (ensuring that

proper length is maintained) with one screw proximal and one screw distal to the nonunion, then use full-length fluoroscopic views or radiographs of the forearm to ensure restoration of length, bow, and joint alignment.

■ Compare with the contralateral forearm.

■ Insert the remaining screws.

■ Ideally, screws are not placed into the graft itself and the graft is stabilized by the compression created by the plate (TECH FIG 4).

■ Close the wound routinely and apply an above-elbow or

sugartong splint.

TECH FIG 4 • Modified Nicoll technique with tricortical iliac crest graft. The graft is chamfered, allowing the graft to be compressed as the plate is applied.

PEARLS AND PITFALLS

Indications ■ Careful evaluation of the patient’s pain and functional limitations must be done before surgical management is planned.

Radiographs ■ Differentiation should be made between hypertrophic and atrophic nonunions, as treatment differs.

■ Contralateral radiographs must be used to determine the appropriate length of the forearm bones and degree of radial bow.

■ Anatomic restoration of length and bow is necessary to allow full rotational motion of the forearm.

Diagnosis of infection ■ A complete preoperative infection workup should be done for all patients with a nonunion.

■ A negative preoperative workup does not rule out infection.

■ An intraoperative infection workup, including Gram stain and culture, should be performed and an alternative plan should be available if infection is encountered.

Nonunion site preparation ■ Débridement of all necrotic, sclerotic, and avascular tissue from the nonunion site is essential.

■ Opening the sclerotic bone ends and gentle reaming of the medullary canals promotes ingrowth of medullary blood vessels.

■ Periosteal stripping and cautery must be minimized to preserve periosteal blood supply.

Graft selection ■ Defects up to 3 cm are successfully managed with cancellous autograft and appropriate fixation.

■ Bone graft substitutes may offer alternatives to autograft, but no comparative studies exist at this time.

Compression of structural ■ Compression must be created across all structural grafts. grafts

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

■ The longer motion is delayed after surgery, the greater the chance the patient will develop stiffness. Therefore, early active range of motion (ROM) should be initiated at the first postoperative visit, except in cases with more tenuous fixation.

■ Use of the arm for activities of daily living is encouraged.

■ If the patient has difficulty in achieving satisfactory ROM with active, active-assisted, and gentle passive ROM, static progressive splints may be used.

■ Having the patient sleep in a static extension splint may significantly improve elbow extension.

■ Heavy lifting, pushing, and weight bearing are delayed until radiographic evidence of healing is present, often 3 to

6 months after the index procedure.

OUTCOMES

■ When precise surgical techniques are used, such as creating stable compression across structural grafts, high rates of union are expected.

■ Rates of healing from 95% to 100% are reported for all of the methods described in this chapter.3,8,9

■ Failure of union is related to recurrence of previous infection in nearly all cases. The prognosis for infected nonunions should be guarded.

■ Patient satisfaction does not correlate directly with bony healing. In multiple studies only two thirds of patients achieved good or excellent results.3,5,8,9

■ Unsatisfactory results are associated with poor postoperative motion in the majority of cases.

■ Other injuries to the upper extremity (common in highenergy trauma associated with nonunions) contributed to unsatisfactory overall function in a minority of patients.9,10

■ Because nonunion of the forearm diaphysis is a rare condition, no comparative studies of treatment methods exist, including the use of bone graft substitutes.

COMPLICATIONS

■ Infection

■ Graft displacement

■ Recurrent nonunion and hardware failure

■ Loss of motion

■ Synostosis

■ Pain or other complications at the autograft harvest site

REFERENCES

1. Adani R, Delcroix L, Innocenti M, et al. Reconstruction of large posttraumatic skeletal defects of the forearm by vascularized free fibular graft. Microsurgery 2004;24:423–429.

2. Chapman MW, Gordon JE, Zissimos AG. Compression-plate fixation of acute fractures of the diaphyses of the radius and ulna. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1989;71A:159–169.

3. Davey PA, Simonis RB. Modification of the Nicoll bone-grafting technique for nonunion of the radius and/or ulna. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002;84B:30–33.

4. Dell PC, Sheppard JE. Vascularized bone grafts in the treatment of infected forearm nonunion. J Hand Surg Am 1984;9A:653–658.

5. Grace TG, Eversman WW. The management of segmental bone loss associated with forearm fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980;62A:

1150–1155.

6. Jupiter JB, Gerhard HJ, Guerrero J, et al. Treatment of segmental defects of the radius with use of the vascularized osteoseptocutaneous fibular autogenous graft. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997;79A:

542–550.

7. Moed BR, Kellam JF, Foster JR, et al. Immediate internal fixation of open fractures of the diaphysis of the forearm. J Bone Joint Surg Am

1986;68A:1008–1017.

8. Moroni AG, Rollo G, Guzzardella M, et al. Surgical treatment of isolated forearm non-union with segmental bone loss. Injury 1997;28:

497–504.

9. Ring D, Allende C, Jafarnia K, et al. Ununited diaphyseal forearm fractures with segmental defects: plate fixation and autogenous cancellous bone-grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86A:

2440–2445.

10. Ring D, Jupiter JB, Gulotta L. Atrophic nonunions of the proximal ulna. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;409:268–274.

11. Ring D, Rhim R, Carpenter C, et al. Comminuted diaphyseal fractures of the radius and ulna: does bone grafting affect nonunion rate? J Trauma 2005;59:436–440.

12. Safoury Y. Free vascularized fibula for the treatment of traumatic bone defects and nonunions of the forearm bones. J Hand Surg Br

2005;30B:67–72.